23 Aug. 2025: Trouw – Activist Andy Hall drie jaar na het WK in Qatar gearresteerd (Dutch Version)

Original Source: Trouw – by Matthijs van Dam 23rd August 2025

De Britse mensenrechtenactivist Andy Hall werd onlangs in Qatar gearresteerd omdat hij mails had rondgestuurd over ‘moderne slavernij’ bij het WK voetbal. Hij kon maar net ontkomen aan de cel. ‘Van Qatar verwachtte ik niets, maar dat mijn eigen overheid mij negeerde, maakte me woedend.’

Hij voelde ’s ochtends vroeg al nattigheid bij de incheckbalie van Qatar Airways. De Britse mensenrechtenactivist Andy Hall wilde op 1 juli naar Qatar vliegen voor een brainstorm met een collega. Ze wilden een strategie bedenken voor bedrijven die zich schuldig maken aan uitbuiting bij de bouw van het WK voetbal van 2034, in Saudi Arabië. Maar de grondstewardess kreeg een foutmelding toen ze Halls paspoort screende. De Brit appte zijn advocaat. Dit had hij nog nooit gezien. Die raadde hem sterk af het vliegtuig naar Doha te nemen. Hall, telefonisch: “Ik appte terug: ‘Nee nee nee, ik heb niets verkeerds gedaan’. Hij kreeg ineens groen licht van de stewardess en ging als laatste aan boord. Hall concentreert zich als mensenrechtenactivist vooral op de problematiek van dwangarbeid door migranten en op de betrokkenheid van westerse bedrijven in de productieketen. Rond het WK voetbal in Qatar in 2022 onderzocht hij hoe Nepalese arbeidsmigranten daar zonder de juiste visums werkten en veel moesten betalen voor emplooi in de Golfstaat. Zij werkten onder meer in de stadionbouw voor het toernooi.

Felle discussies

De Brit werkte ook een tijdje voor een Londens advocatenkantoor dat ethische evaluaties uitvoerde voor het Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy, de toernooiorganisatie van het WK. Nadat Hall erachter kwam dat het comité niet ethisch met arbeidsmigranten omging en hij op Linkedin in felle discussies verzeild raakte met comitéleden, werd hij naar eigen zeggen uit zijn functie bij het kantoor ontheven.

Het voorgevoel van Halls advocaat bleek terecht. Na de landing in Doha werd hij bij de douane opnieuw tegengehouden en in hechtenis genomen. Drie dagen voor de WK-fi nale van 2022 had de Qatarese rechter hem bij verstek veroordeeld tot een maand cel voor laster op basis van de cybercriminaliteitswet. Hall wist van niets. Zijn ‘vergrijp’ was het doorsturen van een aantal mails naar de Qatarese overheid die Hall een maand voor het WK had gekregen van een klokkenluider. Daarin stond dat een Qatarees bedrijf zich rond het toernooi schuldig had gemaakt aan ‘moderne slavernij’. De arrestatie laat zien hoe Qatar drie jaar na het door mensenrechtenschendingen omstreden WK nog steeds achter critici aangaat. Halls zaak is uniek, zegt Nick McGeehan. Hij is directeur van Fairsquare, een mensenrechtenorganisatie die zichconcentreert op het Midden-Oosten.

‘Ik zei dat ik helemaal niks ging tekenen, want ik kon hetdocument niet lezen’

Hij is bekend met de zaak. Voor het WK werden regelmatig journalisten en activisten opgepakt in Qatar, zegt McGeehan, vaak op basis van die cybercriminaliteitswet. Dit is de eerste arrestatie na het toernooi, voor zover hij weet. In de correspondentie tussen Hall en de Britse overheid noemt de regering de arrestatie ‘een poging om activisten af te schrikken zich uit te spreken voor migranten in Qatar’. Hall werd na zijn aanhouding meegenomen naar het kantoor van de openbaar aanklager op het vliegveld, naast de douane. Daar werd hij, naar eigen zeggen, onder druk gezet door agenten om een document te ondertekenen, geschreven in het Arabisch. “Ik zei dat ik helemaal niks ging tekenen, want ik kon het niet lezen.”

In dat document, in bezit van Trouw, staat dat Hall met ondertekening zou erkennen dat hij is veroordeeld tot een maand cel voor laster. Correspondentie met de Britse ambassade in Doha bevestigt dat hem ook een advocaat en tolk werden ontzegd, ondanks herhaaldelijke verzoeken.

Zijn redding, zegt Hall, was een bezoekje aan het toilet. In dat hokje appte hij zoveel mensen als hij kon: de Internationale Arbeidsorganisatie, collega’s van andere ngo’s, zijn advocaat. Die vroegen hem om een foto van het document, dat hij pas in tweede instantie van zijn bewakers mocht fotograferen. Hall had de foto al rondgestuurd toen hij die van de bewakers ineens weer moest verwijderen. Van zijn contacten kreeg hij dringend advies niet te tekenen. Anders zou hij direct naar de gevangenis gaan. Terwijl Hall uren in detentie zat op het vliegveld, werd zijn arrestatie bekend bij Britse media. “Iemand appte me: de BBC heeft over je zaak getweet.” Hij hoorde dat de BBC, The Guardian, AP en AFP de Qatarese overheid hadden benaderd met vragen over de arrestatie. Niet veel later kreeg Hall ineens zijn paspoort terug. Of hij naar een hotel in Doha wilde dan wel met het eerste vliegtuig het land uit; het maakte de aanklager niet uit. Als hij maar wegging.

Geen rechtsstaat

Correspondentie met de Britse overheid, ingezien door Trouw, bevestigt dat de Qatarezen Hall lieten gaan vanwege zijn ‘internationale roep om hulp’. “Het slaat eigenlijk nergens op dat ze me daardoor ineens vrijlieten. Het laat zien dat Qatar nog steeds geen functionerende rechtsstaat heeft”, zegt Hall. Hij is zeer kritisch op de rol van de Britse overheid. Met de Britse ambassade in Doha legde hij na zijn arrestatie telefonisch contact. Die vertelde hem, zo staat in de verslaglegging van dat gesprek door het Britse ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken, dat het personeel niet over de kennis beschikte om juridisch advies te geven. Een tolk en een advocaat regelen was ‘onrealistisch’. Hij kon beter vrienden en familie vragen om een Qatarese advocaat in te schakelen. Volgens Halls advocaat Michael Polak is het ‘de plicht van de Britse overheid om ervoor te zorgen dat onderdanen niet gediscrimineerd worden in een staat die hen in afwezigheid heeft veroordeeld’. Volgens Hall adviseerde de ambassade hem ook het document te ondertekenen en de Qatarese gevangenis in te gaan. Dan had de ambassade iemand op ‘welzijnsbezoek’ kunnen sturen. In Engeland is het normaal om bij een hulpvraag in het buitenland het parlementslid uit het eigen kiesdistrict in te schakelen. Die persoon reageerde pas weken later op Halls mails. Hall wijt dat zelf aan de zakelijke belangen die dat parlementslid in het Midden-Oosten heeft. “Ik weet hoe zakendoen in die regio werkt. Als je daar veel geld geïnvesteerd hebt, los je problemen liever stilletjes op.”

De verantwoordelijke voor het Midden-Oosten op het ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken beantwoordde Halls mails pas na twee weken. Hall had toen al tien mails verstuurd. De ambtenaar biedt in haar antwoord excuses aan voor de late reactie, erkent dat zij veel eerder had moeten reageren en dat zulke situaties in de toekomst niet meer zullen voorkomen. Ook schrijft ze dat ‘die moeilijke tijd beangstigend heeft moeten zijn’ voor Hall.

“Ik was helemaal niet bang, ik was verbaasd”

“De Britse overheid irriteert me meer dan die van Qatar. Van Qatar verwachtte ik niets, maar dat mijn eigen overheid mij negeerde, maakte me woedend.”

‘Het was duidelijk dat de Britse overheid geen problemen met Qatar wilde’

Halls zaak doet denken aan die van Abdullah Ibhais, voormalig communicatiemanager van de WK-organisatie. Hij werd opgepakt na een gefabriceerde aanklacht van fraude, nadat Ibhais weigerde arbeidsprotesten onder het tapijt te vegen. Hij vroeg de Nederlandse ambassade acht keer om hulp, maar kreeg die niet. Achter de schermen, zo bleek uit interne documenten, speelden vooral handelsbelangen en de relatie met Qatar een belangrijke rol om niet in te grijpen. “Voor de Britse overheid

is handel ook prioriteit nummer één. Daarbovenop bemiddelt Qatar tussen Hamas en Israël. Het was duidelijk dat de Britse overheid geen problemen met Qatar wilde” zegt Hall. Uit angst dat de Qatarezen zich bedachten en hem toch een maand vast zouden zetten, pakte Hall het eerste het beste vliegtuig vanaf Doha naar Bangkok. Hij vroeg nog of dit formeel een deportatie was, wat meestal gebeurt met buitenlanders in Qatar na een strafzaak. De Qatarezen vertelden Hall dat dat niet het geval was en hij een vrijgeleide had gekregen. Dat de Britse overheid in correspondentie blijft volhouden dat Hall gedeporteerd is, bewijst voor hem dat ze zich nooit echt in zijn zaak geïnteresseerd hebben.

Arbitraire detentie

Opvallend is dat verschillende advocaten hem niet wilden bijstaan in een hoger beroep tegen zijn veroordeling, zo blijkt uit de correspondentie, omdat Hall de media heeft gezocht. Zij werken liever zonder publieke aandacht. Ook de Britse overheid is niet bereid hem te helpen bij het aanvechten van zijn veroordeling. Met een Qatarese advocaat gaat Hall dat alsnog doen. Ook diende hij deze week bij de Verenigde Naties een aanklacht in tegen de Qatarese staat wegens arbitraire detentie. Hij financiert de juridische kosten via crowdfunding. Hoger beroep indienen is belangrijk, zegt Hall, omdat zo’n veroordeling hem hindert in zijn werk als mensenrechtenactivist.

“Het tast mijn geloofwaardigheid aan. Maar het is ook een middelvinger en een zorgwekkend signaal naar de internationale gemeenschap, klokkenluiders en activisten. Dit gebeurt er als je je mond opentrekt.”

23 Aug 2025: Trouw – Activist Andy Hall arrested three years after the World Cup in Qatar (English Version)

Original Source: Trouw – by Matthijs van Dam 23rd August 2025

British human rights activist Andy Hall was recently arrested in Qatar for sending emails about “modern slavery” surrounding the World Cup. He narrowly avoided jail. “I didn’t expect anything from Qatar, but the fact that my own government ignored me made me furious.”

He sensed something was wrong early that morning at the Qatar Airways check-in desk. British human rights activist Andy Hall was planning to fly to Qatar on July 1st for a brainstorming session with a colleague. They wanted to devise a strategy for companies involved in exploitative practices during the construction of the 2034 World Cup in Saudi Arabia. But the flight attendant received an error message when she screened Hall’s passport. He had never seen this before. He strongly advised against taking the plane to Doha. Hall, on the phone: “I texted back: ‘No, no, no, I didn’t do anything wrong.'” He suddenly got the green light from the flight attendant and boarded last.

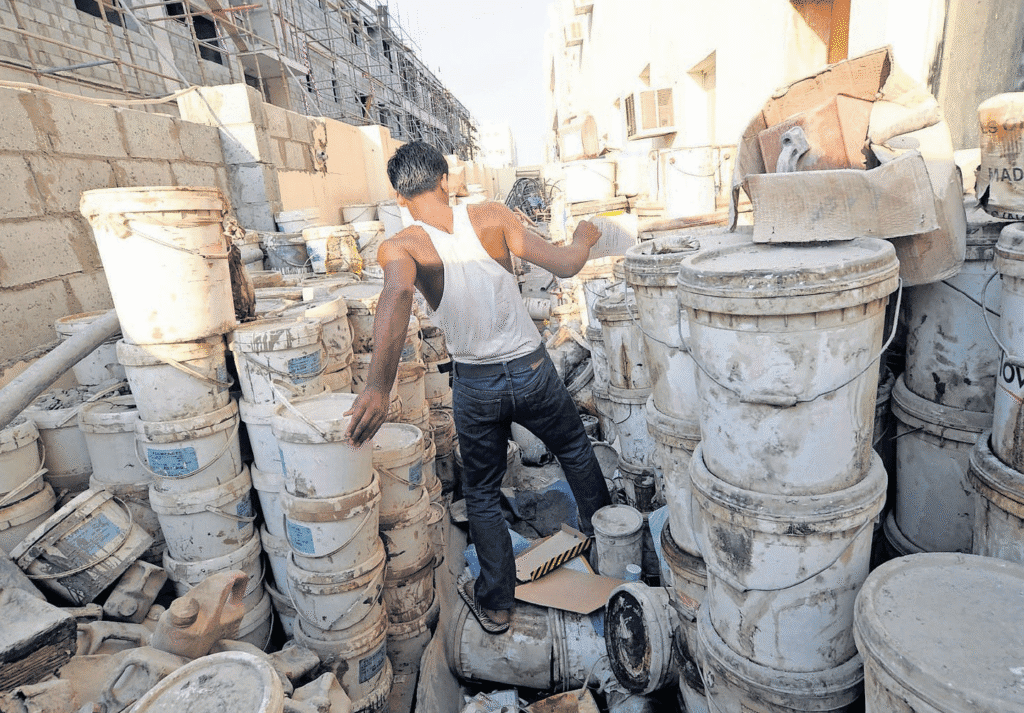

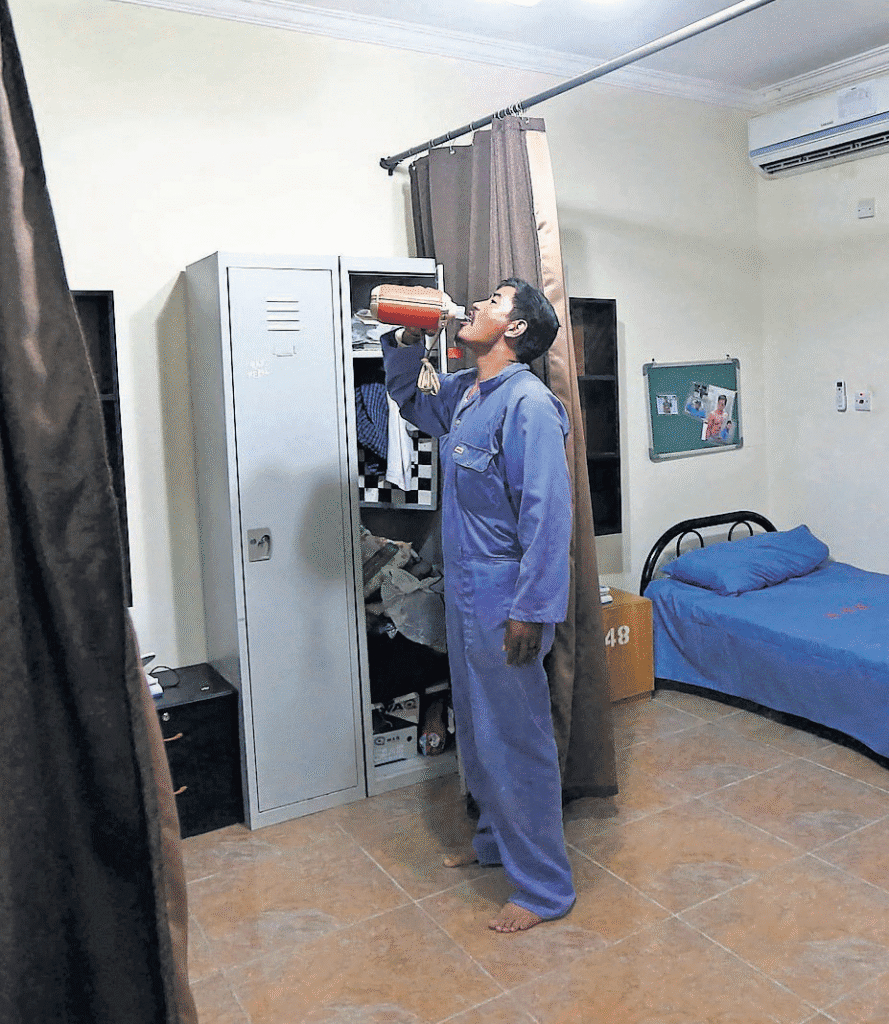

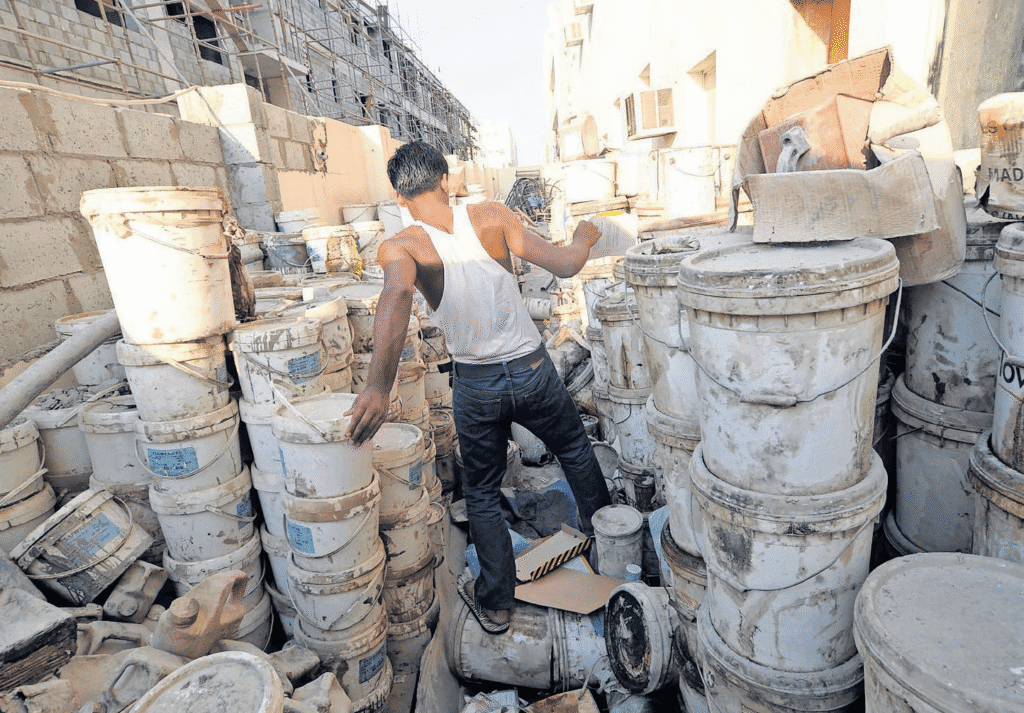

As a human rights activist, Hall focuses primarily on the issue of forced migrant labor and the involvement of Western companies in the supply chain. Around the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, he investigated how Nepalese migrant workers were working there without the proper visas and were being paid excessively for employment in the Gulf state. They worked, among other things, on stadium construction for the tournament.

Fierce discussions

The Briton also worked for a time for a London law firm that conducted ethics reviews for the Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy, the World Cup tournament organizers. After Hall discovered that the committee wasn’t dealing ethically with migrant workers and became embroiled in heated discussions with committee members on LinkedIn, he was, according to his own account, dismissed from his position at the firm.

Hall’s lawyer’s premonition proved correct. After landing in Doha, he was again stopped at customs and taken into custody. Three days before the 2022 World Cup final, a Qatari judge sentenced him in absentia to a month in prison for defamation under the cybercrime law. Hall knew nothing about this. His “offense” was forwarding several emails to the Qatari government that Hall had received from a whistleblower a month before the World Cup. These emails stated that a Qatari company had engaged in “modern slavery” around the tournament. The arrest demonstrates how Qatar continues to pursue critics three years after the World Cup, which was controversial due to human rights violations. Hall’s case is unique, says Nick McGeehan, director of Fairsquare, a human rights organization focused on the Middle East.

I said I wasn’t going to sign anything because I couldn’t read the document.

He’s familiar with the case. Before the World Cup, journalists and activists were regularly arrested in Qatar, says McGeehan, often under the cybercrime law. This is the first arrest since the tournament, as far as he knows. In correspondence between Hall and the British government, the latter calls the arrest “an attempt to deter activists from speaking out for migrants in Qatar.” After his arrest, Hall was taken to the public prosecutor’s office at the airport, next to customs. There, he says, he was pressured by officers to sign a document written in Arabic. “I said I wasn’t going to sign anything because I couldn’t read it.”

That document, obtained by Trouw, states that Hall, by signing it, allegedly acknowledges that he has been sentenced to a month in prison for defamation. Correspondence with the British embassy in Doha confirms that he was also denied a lawyer and interpreter, despite repeated requests.

His salvation, says Hall, was a visit to the restroom. From that cubicle, he texted as many people as he could: the International Labour Organization, colleagues from other NGOs, his lawyer. They asked him for a photo of the document, which his guards only subsequently allowed him to take. Hall had already circulated the photo when the guards suddenly ordered him to delete it. His contacts strongly advised him not to sign, or he would go straight to prison. While Hall was detained for hours at the airport, his arrest became known to the British media. “Someone texted me: the BBC tweeted about your case.” He learned that the BBC, The Guardian, AP, and AFP had contacted the Qatari government with questions about the arrest. Not much later, Hall suddenly got his passport back. Whether he wanted to go to a hotel in Doha or catch the first plane out of the country; it didn’t matter to the prosecutor. As long as he left.

No Rule of Law

Correspondence with the British government, seen by Trouw, confirms that the Qataris released Hall because of his “international plea for help.” “It really doesn’t make sense that they suddenly released me because of that. It shows that Qatar still doesn’t have a functioning rule of law,” says Hall. He is highly critical of the British government’s role. After his arrest, he contacted the British embassy in Doha by phone. According to the British Foreign Office’s report of that conversation, the embassy told him that its staff lacked the expertise to provide legal advice. Arranging an interpreter and a lawyer was “unrealistic.” He would be better off asking friends and family to engage a Qatari lawyer. According to Hall’s lawyer, Michael Polak, it is “the British government’s duty to ensure that its citizens are not discriminated against in a state that has convicted them in their absence.” According to Hall, the embassy also advised him to sign the document and go to Qatari prison. Then the embassy could have sent someone on a “welfare visit.” In England, it’s common practice to contact the Member of Parliament from your own constituency when someone needs help abroad. That person didn’t respond to Hall’s emails for weeks. Hall attributes this to the MP’s business interests in the Middle East. “I know how doing business works in that region. If you’ve invested a lot of money there, you prefer to solve problems quietly.”

“I wasn’t scared at all, I was surprised”

“The British government irritates me more than Qatar’s. I expected nothing from Qatar, but the fact that my own government ignored me made me furious.”

“It was clear that the British government did not want any problems with Qatar.”

Hall’s case is reminiscent of that of Abdullah Ibhais, the former communications manager for the World Cup organizers. He was arrested on a fabricated charge of fraud after Ibhais refused to cover up labor protests. He asked the Dutch embassy for help eight times, but received none. Behind the scenes, internal documents revealed, trade interests and the relationship with Qatar played a significant role in preventing him from intervening. “For the British government, trade is also the number one priority.

Moreover, Qatar mediates between Hamas and Israel. It was clear that the British government didn’t want any problems with Qatar,” says Hall. Fearing that the Qataris would change their minds and detain him for a month after all, Hall took the first available plane from Doha to Bangkok. He asked if this was formally a deportation, which is usually done with foreigners in Qatar after a criminal case. The Qataris told Hall that it wasn’t and that he had been given a safe conduct. The fact that the British government continues to insist in correspondence that Hall was deported proves to him that they were never really interested in his case.

Arbitrary detention

It’s striking that several lawyers declined to represent him in an appeal against his conviction, according to the correspondence, because Hall sought media attention. They prefer to work without public attention. The British government is also unwilling to assist him in appealing his conviction. Hall plans to do so with the help of a Qatari lawyer. This week, he also filed a complaint with the United Nations against the Qatari state for arbitrary detention. He is financing the legal costs through crowdfunding. Filing an appeal is important, says Hall, because such a conviction would hinder his work as a human rights activist.

“It damages my credibility. But it’s also a middle finger and a worrying signal to the international community, whistleblowers, and activists. This is what happens when you speak out.”

See full PDF article linked below from Trouw: