The last week has seen the high-profile release of Ian Urbina’s forced labour investigation linking global seafood retailers and supermarkets to Chinese seafood supply chains. See below the original articles and some related response articles.

The Crimes Behind the Seafood You Eat

Original Article: The New Yorker by Ian Urbina – 9th October 2023.

DANIEL ARITONANG GRADUATED from high school in May, 2018, hoping to find a job. Short and lithe, he lived in the coastal village of Batu Lungun, Indonesia, where his father owned an auto shop. Aritonang spent his free time rebuilding engines in the shop, occasionally sneaking away to drag-race his blue Yamaha motorcycle on the village’s back roads. He had worked hard in school but was a bit of a class clown, always pranking the girls. “He was full of laughter and smiles,” his high-school math teacher, Leni Apriyunita, said. His mother brought homemade bread to his teachers’ houses, trying to help him get good grades and secure work; his father’s shop was failing, and the family needed money. But, when Aritonang finished high school, youth unemployment was above sixteen per cent. He considered joining the police academy, and applied for positions at nearby plastics and textile factories, but never got an offer, disappointing his parents. He wrote on Instagram, “I know I failed, but I keep trying to make them happy.” His childhood friend Hengki Anhar was also scrambling to find work. “They asked for my skills,” he said recently, of potential employers. “But, to be honest, I don’t have any.”

At the time, many villagers who had taken jobs as deckhands on foreign fishing ships were returning with enough money to buy motorcycles and houses. Anhar suggested that he and Aritonang go to sea, too, and Aritonang agreed, saying, “As long as we’re together.” He intended to use the money to fix up his parents’ house or maybe to start a business. Firmandes Nugraha, another friend, worried that Aritonang was not cut out for hard labor. “We took a running test, and he was too easily exhausted,” he said. But Aritonang wouldn’t be dissuaded. A year later, in July, he and Anhar travelled to the port city of Tegal, and applied for work through a manning agency called PT Bahtera Agung Samudra. (The agency seems not to have a license to operate, according to government records, and did not respond to requests for comment.) They handed over their passports, copies of their birth certificates, and bank documents. At eighteen, Aritonang was still young enough that the agency required him to provide a letter of parental consent. He posted a picture of himself and other recruits, writing, “Just a bunch of common folk who hope for a successful and bright future.”

For the next two months, Aritonang and Anhar waited in Tegal for a ship assignment. Aritonang asked Nugraha to borrow money for them, saying that the pair were struggling to buy food. Nugraha urged him to come home: “You don’t even know how to swim.” Aritonang refused. “There’s no other choice,” he wrote, in a text. Finally, on September 2, 2019, Aritonang and Anhar were flown to Busan, South Korea, to board what they thought would be a Korean ship. But when they got to the port they were told to climb aboard a Chinese vessel—a rusty, white-and-red-keeled squid ship called the Zhen Fa 7.

In the past few decades, partly in an effort to project its influence abroad, China has dramatically expanded its distant-water fishing fleet. Chinese firms now own or operate terminals in ninety-five foreign ports. China estimates that it has twenty-seven hundred distant-water fishing ships, though this figure does not include vessels in contested waters; public records and satellite imaging suggest that the fleet may be closer to sixty-five hundred ships. (The U.S. and the E.U., by contrast, have fewer than three hundred distant-water fishing vessels each.) Some ships that appear to be fishing vessels press territorial claims in contested waters, including in the South China Sea and around Taiwan. “This may look like a fishing fleet, but, in certain places, it’s also serving military purposes,” Ian Ralby, who runs I.R. Consilium, a maritime-security firm, told me. China’s preëminence at sea has come at a cost. The country is largely unresponsive to international laws, and its fleet is the worst perpetrator of illegal fishing in the world, helping drive species to the brink of extinction. Its ships are also rife with labor trafficking, debt bondage, violence, criminal neglect, and death. “The human-rights abuses on these ships are happening on an industrial and global scale,” Steve Trent, the C.E.O. of the Environmental Justice Foundation, said.

It took a little more than three months for the Zhen Fa 7 to cross the ocean and anchor near the Galápagos Islands. A squid ship is a bustling, bright, messy place. The scene on deck looks like a mechanic’s garage where an oil change has gone terribly wrong. Scores of fishing lines extend into the water, each bearing specialized hooks operated by automated reels. When they pull a squid on board, it squirts warm, viscous ink, which coats the walls and floors. Deep-sea squid have high levels of ammonia, which they use for buoyancy, and a smell hangs in the air. The hardest labor generally happens at night, from 5 p.m. until 7 a.m. Hundreds of bowling-ball-size light bulbs hang on racks on both sides of the vessel, enticing the squid up from the depths. The blinding glow of the bulbs, visible more than a hundred miles away, makes the surrounding blackness feel otherworldly. “Our minds got tested,” Anhar said.

The captain’s quarters were on the uppermost deck; the Chinese officers slept on the level below him, and the Chinese deckhands under that. The Indonesian workers occupied the bowels of the ship. Aritonang and Anhar lived in cramped cabins with bunk beds. Clotheslines of drying socks and towels lined the walls, and beer bottles littered the floor. The Indonesians were paid about three thousand dollars a year, plus a twenty-dollar bonus for every ton of squid caught. Once a week, a list of each man’s catch was posted in the mess hall to encourage the crew to work harder. Sometimes the officers patted the Indonesian deckhands on their heads, as though they were children. When angry, they insulted or struck them. The foreman slapped and punched workers for mistakes. “It’s like we don’t have any dignity,” Anhar said.

The ship was rarely near enough to land to get cell reception, and, in any case, most deckhands didn’t have phones that would work abroad. Chinese crew members were occasionally allowed to use a satellite phone on the ship’s bridge. But when Aritonang and other Indonesians asked to call home the captain refused. After a couple of weeks on board, a deckhand named Rahman Finando got up the nerve to ask whether he could go home. The captain said no. A few days later, another deckhand, Mangihut Mejawati, found a group of Chinese officers and deckhands beating Finando, to punish him for asking to leave. “They beat his whole body and stepped on him,” Mejawati said. The other deckhands yelled for them to stop, and several jumped into the fray. Eventually, the violence ended, but the deckhands remained trapped on the ship. Mejawati told me, “It’s like we’re in a cage.”

The Uyghurs Forced to Process the World’s Seafood

China forces minorities from Xianjiang to work in industries around the country. As it turns our, this includes much of the seafood sent to America and Europe.

Read full story here – Original Article: The New Yorker by Ian Urbina – 9th October 2023.

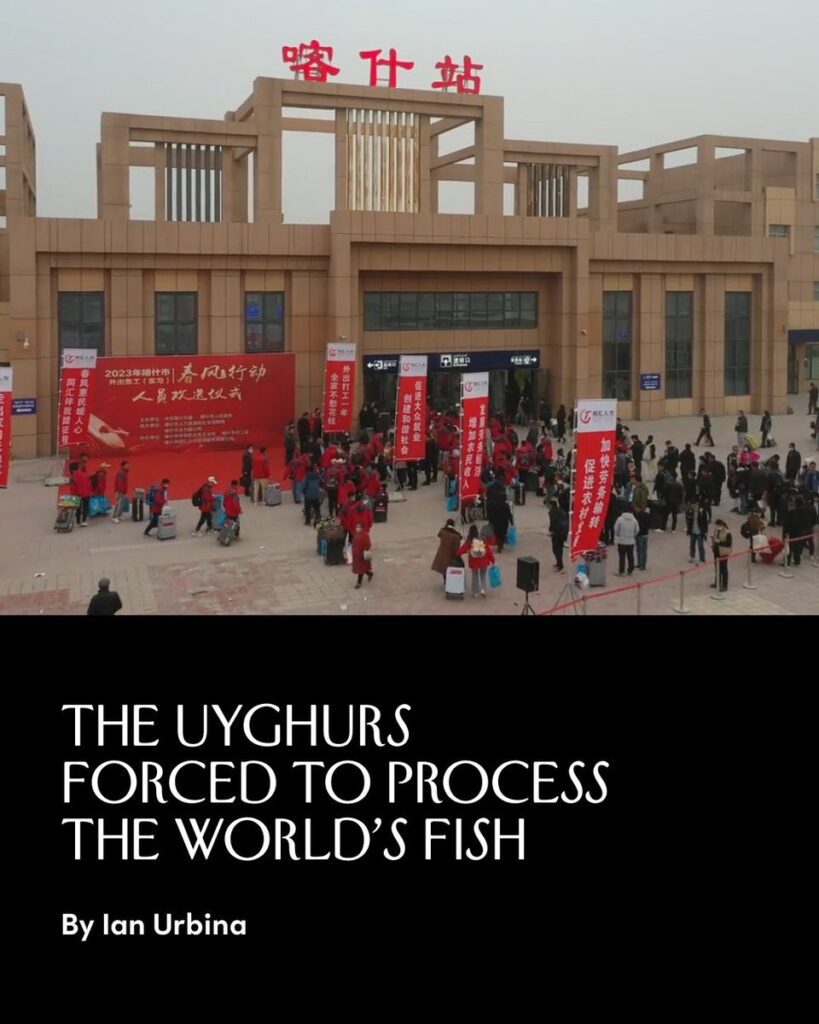

On a cloudy morning this past April, more than eighty men and women, dressed in matching red windbreakers, stood in orderly lines in front of the train station in Kashgar, a city in Xinjiang, China. The people were Uyghurs, one of China’s largest ethnic minorities, and they stood with suitcases at their feet and dour expressions on their faces, watching a farewell ceremony held in their honor by the local government. A video of the event shows a woman in a traditional red-and-yellow dress and doppa cap pirouetting on a stage. A banner reads “Promote Mass Employment and Build Societal Harmony.” At the end of the video, drone footage zooms out to show trains waiting to take the group away. The event was part of a vast labor-transfer program run by the Chinese state, which forcibly sends Uyghurs to work in industries across the country, including processing seafood that is then exported to the United States and Europe. “It’s a strategy of control and assimilation,” Adrian Zenz, an anthropologist who studies internment in Xinjiang, said. “And it’s designed to eliminate Uyghur culture.”

The labor program is part of a wider agenda to subjugate a historically restive people. China is dominated by the Han ethnic group, but more than half the population of Xinjiang, a landlocked region in northwestern China, is made up of minorities—most of them Uyghur, but some Kyrgyz, Tajik, Kazakh, Hui, or Mongol. Uyghur insurgents revolted throughout the nineteen-nineties, and bombed police stations in 2008 and 2014. In response, China ramped up a broad program of persecution, under which Muslim minorities could be detained for months or years for acts such as reciting a verse of the Quran at a funeral or growing a long beard. By 2017, the government was collecting DNA samples, fingerprints, iris scans, and blood types from all Xinjiang residents between the ages of twelve and sixty-five, and in recent years it combined these biological records with mass surveillance data sourced from Wi-Fi sniffers, CCTV, and in-person visits. The government has placed millions of Uyghurs in “reëducation” camps and detention facilities, where they have been subjected to torture, beatings, and forced sterilization. The U.S. government has described the country’s actions in Xinjiang as a form of genocide.

In the early two-thousands, China began transferring Uyghurs to work outside the region as part of an initiative that would later be known as Xinjiang Aid. The region’s Party secretary noted that the program would promote “full employment” and “ethnic interaction, exchange and blending.” But Chinese academic publications have described it as a way to “crack open” the “solidified problem” of Uyghur society in Xinjiang, where the state sees the “large number of unemployed Uyghur youths” as a “latent threat.” In 2019, researchers at Nankai University in China, who were given privileged access to information about the program, wrote a report that was inadvertently published online, describing the transfers as “an important method to reform, meld, and assimilate” the Uyghur community. Julie Millsap, from the Uyghur Human Rights Project, noted that, through the program, the state can “orchestrate and restrict all aspects of Uyghurs’ lives.” (Officials at China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not respond to questions about the program, but Wang Wenbin, a spokesperson, recently said that the allegation of forced labor is “nothing but an enormous lie propagated by people against China.”) Between 2014 and 2019, according to government statistics, Chinese authorities annually relocated more than ten per cent of Xinjiang’s population—or over two and a half million people—through labor transfers; some twenty-five thousand people a year were sent out of the region. The effect has been enormous: between 2017 and 2019, according to the Chinese government, birth rates in Xinjiang declined by almost half.

In 2021, Congress passed the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, which declared that all goods produced “wholly or in part” by workers in Xinjiang or by ethnic minorities from the region should be presumed to have involved state-imposed forced labor, and are therefore banned from entering the U.S. The law had a major impact. Since June of last year, U.S. Customs and Border Protection has detained more than a billion dollars’ worth of goods connected to Xinjiang, including electronics, clothing, and pharmaceuticals. But, until now, the seafood industry has largely escaped notice. The U.S. imports roughly eighty per cent of its seafood, and China supplies more than any other country. As of 2017, half of the fish that have gone into fish sticks served in American public schools have been processed in China, according to the Genuine Alaska Pollock Producers. But the many handoffs between fishing boats, processing plants, and exporters make it difficult to track the origin of seafood. Shandong Province, a major seafood-processing hub along the eastern coast of China, is more than a thousand miles away from Xinjiang—which may have helped it evade scrutiny. As it turns out, at least a thousand Uyghurs have been sent to work in seafood-processing factories in Shandong since 2018. “It’s door-to-door,” Zenz said. “They literally get delivered from the collection points in Xinjiang to the factory.”

Foreign journalists are generally forbidden from freely reporting in Xinjiang. In addition, censors scrub the Chinese Internet of critical and non-official content about Uyghur labor. I worked with a research team to review hundreds of pages of internal company newsletters, local news reports, trade data, and satellite imagery. We watched thousands of videos uploaded to the Internet—mostly to Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok—which appear to show Uyghur workers from Xinjiang; we verified that many of the users had initially registered in Xinjiang, and we had specialists review the languages used in the videos. We also hired investigators to visit some of the plants. These sources provided a glimpse into a system of forced Uyghur labor behind the fish that much of the world eats.

The transfers usually start with a knock on the door. A “village work team,” made up of local Party officials, enter a household and engage in “thought work,” which involves urging Uyghurs to join government programs, some of which entail relocations. Officials often have onboarding quotas, and representatives from state-owned corporations—including the Xinjiang Zhongtai Group, a Fortune 500 conglomerate, which is involved in coördinating labor transfers—sometimes join the house visits. Wang Hongxin, the former chairman of Zhongtai, which facilitated the “employment” of more than four thousand workers from southern Xinjiang in the past few years, described his company’s recruitment efforts in rosy terms: “Now farmers in Siyak have a strong desire to go out of their homes and find employment.” (The company did not respond to requests for comment for this piece.)

The official narrative suggests that Uyghur workers are grateful for employment opportunities, and some likely are. In an interview with state media, one Uyghur worker noted that she and her husband now made twenty-two thousand dollars a year at a seafood plant, and that the factory provided “free board and lodging.” But a classified internal directive from Kashgar Prefecture’s Stability Maintenance Command, from 2017, indicates that people who resist work transfers can be punished with detainment. Zenz told me about a woman from Kashgar who refused a factory assignment because she had to take care of two small children, and was detained as a result. Another woman who refused a transfer was put in a cell for “non-coöperation.” And the state has other methods of exerting pressure. Children and older adults are often sent to state-run facilities; family lands can be confiscated. According to a 2021 Amnesty International report, one former internment camp detainee said, “I learned that if one family [member] was in a camp you have to work so father or husband can get out quickly.”

Once people are recruited, they are rounded up. In February, 2022, for example, thousands of Uyghurs were taken to a “job fair” next to an internment camp in southwestern Xinjiang. A video of a similar event shows people in neat lines, signing contracts while monitored by people who appear to be officials in army fatigues. Many transfers are carried out by train or plane. Pictures show Uyghurs with red flowers pinned to their jackets—a common symbol of celebration—boarding China Southern Airlines flights chartered by the authorities in Xinjiang. (The airline did not respond to requests for comment.)

Sometimes, transfers are motivated by labor demands. In March, 2020, the Chishan Group, one of China’s leading seafood companies, published an internal newsletter describing what it called the “huge production pressure” caused by the pandemic. That October, Party officials from the local antiterrorist detachment of the public-security bureau and the human-resources-and-social-security bureau, which handles work transfers, met twice with executives to discuss how to find additional labor for the company. Several months later, Chishan agreed to accelerate transfers to its plants. Wang Shanqiang, the deputy general manager at Chishan, said in a corporate newsletter that “the company looks forward to migrant workers from Xinjiang arriving soon.” (The Chishan Group did not respond to requests for comment.)

An advertisement aimed at factory owners, posted on a Chinese online forum, promises that, when workers arrive, they will be kept under “semi-military-style management.” Videos from seafood plants show that many workers from Xinjiang live in dormitories. Workers are reportedly often kept under the watch of security personnel. A worker in Fujian Province told Bitter Winter, an online magazine, that Uyghur dorms were often searched; if a Quran was found, he recalled, its owner could be sent to a reëducation camp. In a Chishan newsletter from December, 2021, the company listed the management of migrant workers as a “major” source of risk; another newsletter underscores the importance of supervising them at night and during holidays to prevent “fights, drunk disturbances, and mass incidents.”

For workers who come from rural areas of Xinjiang, the transition can be abrupt. New workers, yet another Chishan newsletter explains, are not subject to production quotas, to help them adjust. But, after a month, factory officials begin monitoring their daily output to increase “enthusiasm.” One factory has special teams of managers responsible for those who “do not adapt to their new life.” Sometimes, new Uyghur workers are paired with older ones who are assigned to “keep abreast of the state of mind of the new migrant workers.” Many Xinjiang laborers are subjected to “patriotic education.” Pictures published by a municipal agency show minority workers from Xinjiang at Yantai Sanko Fisheries studying a speech by Xi Jinping and learning about “the party’s ethnic policy.”(Yantai Sanko did not respond to requests for comment.) Companies sometimes try to ease this transition by offering special accommodations. In an effort to boost morale, some large factories provide separate canteens and Uyghur food for transferred workers. Occasionally, factories hold festive events that include dancing and music. Footage from inside one plant shows Uyghurs dancing in the cafeteria, surrounded by uniformed security guards.

Workers from other industries who have escaped the labor-transfer programs are sometimes explicitly critical about their treatment. One Uyghur man was released from a reëducation camp only to be transferred to a garment factory. “We didn’t have a choice but to go there,” he told Amnesty International, according to its 2021 report. A woman from Xinjiang named Gulzira Auelkhan was forced to work in a glove factory. She was punished for crying or spending a couple of extra minutes in the restroom by being placed in the “tiger chair,” which kept her arms and legs pinned down—a form of torture. “I spent six to eight hours in the tiger chair the first time because I didn’t follow the rules,” she said. “The police claimed I had mental issues and wasn’t in the right mind-set.”

But the Uyghurs still at factories are monitored closely, and one of the few ways to get a peek into their lives is through their social-media posts. After arriving in Shandong, they sometimes take selfies by the water; Xinjiang is the farthest place on earth from the ocean. Some post Uyghur songs with mournful lyrics. These could, of course, simply be snippets of sentimental music. But researchers have argued that they might also function as ways of conveying cryptic messages of suffering, while bypassing Chinese censors. As a 2015 analysis concluded, “Social commentary and critique are veiled through the use of metaphors, sarcasm, and references to traditional Uyghur sayings and cultural aspects that only an insider or someone very familiar with the Uyghur culture and community would recognize.” In more recent years, government surveillance and censorship have only increased.

One middle-aged Uyghur man, who went on to work in a Shandong seafood plant, filmed himself sitting in an airport departure lounge in March, 2022, and set the footage to the song “Kitermenghu” (“I Shall Leave”). He cut away just before a section of the song that anybody familiar with it would know, which includes the line: “Now we have an enemy; you should be careful.” Another Uyghur worker, who had spoken glowingly of the programs in official media reports, one of which featured a photo of him by the sea, posted the same image to Douyin alongside a song that goes, “Why is there a need to suffer more?” A young woman posted a selfie taken in front of a Shandong seafood plant and added an excerpt from an Uyghur pop song: “We’re used to so much suffering,” the lyrics say. “Be patient, my heart. These days will pass.” One slideshow features workers packing seafood into cardboard boxes. A voice-over says, “The greatest joy in life is to defeat an enemy who is many times stronger than you, and who has oppressed you, discriminated against you, and humiliated you.”

In some videos, Uyghur workers express their unhappiness in slightly less veiled terms. One worker posted a video showing himself gutting fish at Yantai Longwin Foods. “Do you think there is love in Shandong?” the voice-over asks. “There is only waking up at five-thirty every morning, non-stop work, and the never-ending sharpening of knives and gutting of fish.” (Yantai Longwin Foods did not respond to a request for comment.)

With the convict sailors of the Chinese fishing empire: “My parents must take back my body”

Original Article: Le Monde by Ian Urbina – 10th October 2023

During their investigation, journalists from The Outlaw Ocean Project discovered that Beijing will stop at nothing to plunder international waters, with the ambition of granting itself sovereignty over these areas of the globe. A titanic undertaking with dizzying environmental and human costs, as illustrated by the shattered destiny of Fadhil, a young Indonesian fisherman.

First, he was very thirsty. Then, seizures. He was too exhausted to sit up and couldn’t even urinate. He vomited everything he swallowed, water and food. Originally from Indonesia, Fadhil, 24, worked on the Wei-Yu 18 , a Chinese squid fishing vessel that operated 285 nautical miles (about 528 kilometers) off the coast of Peru. When he became ill, he begged the team leader to send him ashore for treatment. But he refused, on the grounds that his contract had not ended, simply giving him an equivalent of ibuprofen.

“My parents must get my body back ,” Fadhil whispered to another sailor, Ramadhan Sugandhi, the day before his death, which occurred on September 26, 2019, after almost a month of suffering. The captain then ordered the crew to wrap her remains in a blanket and store her in the cold room – but she turned black there. Less than three days later, Fadhil’s body was placed in a wooden coffin weighted with an anchor chain, and the box tipped into the water. “Seeing this, I was desperate ,” recalls Ramadhan Sugandhi.

Here’s a quick wrap of everywhere the Outlaw Ocean Project investigation has published over the weekend, from Daniel Murphy’s LinkedIn post:

El Pais – https://lnkd.in/egBs5vkg

Ojo Público – https://lnkd.in/eT_6wDTJ

El Estornudo – https://lnkd.in/emnzTsMY

Público (at sea) – https://lnkd.in/e26geQkb

Público (on land) – https://lnkd.in/eHQkeCyV

Helsingin Sanomat – https://lnkd.in/eUpt6j-3

Vrij Nederland – https://lnkd.in/eNndDmsU

De Correspondent – https://lnkd.in/e2ene2Ra

NU.nl – https://lnkd.in/eHMKV3rB

Follow the Money – https://lnkd.in/eyaxeyBx

Il Fatto Quotidiano – https://lnkd.in/estVkFSc

El País Uruguay – https://lnkd.in/er6bW6ZY

See also additional responses:

- Bombshell Outlaw Ocean report finds evidence of seafood processed by forced labor in US supply chain

- Albertsons drops High Liner products after supplier is implicated in forced labor exposé

- Seafood industry cuts ties to Chinese firms accused of using Uyghur labor

- Lund’s Fisheries, PAFCO cease business with Chinese processors named in Outlaw Ocean report

- Social audits for MSC, ASC, BRC certification likely missed evidence of Uyghur forced labor

Lawmakers urge European Commission to take on China’s ‘deplorable’ fishing practices

Original Article: scmp by Finbarr Berminghamin Brussels – 17th October 2023.

Europe is confronting China on futuristic fronts from artificial intelligence to quantum computing, but lawmakers are also pushing Brussels to take on an altogether ancient resource: fish.

In a debate on Monday night, members of the European Parliament railed against China’s industrial fishing practices, asking the union’s secretariat, the European Commission, to do more to counter behaviour described as “deplorable”.

Several members cited labour conditions on Chinese vessels, with some referring to recent media reports about industrial-scale use of Uygur forced labour on fishing vessels. Others cited alleged subsidies in China’s fishing industry for distorting the global supply chain.

The parliament will vote on Tuesday on a resolution that claims that opacity and subsidies in China’s fishing industry “severely undermines the competitiveness of the EU single market”.

“Did you know that part of the fish from forced labour among Uygurs ends up on our plates?”

Caroline Roose, Green Party member of European Parliament

“This has severe economic and labour repercussions for companies in the sector and throughout the supply chain,” the resolution said.

Addressing the debate, the European commissioner for budget and administration, Johannes Hahn, said the commission would launch a study into flags of convenience. Chinese fishing vessels are accused of flying non-Chinese flags to facilitate illegal fishing.

“We want China to move further to effectively prevent and sanction illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing,” Hahn said, adding that the commission would continue to pursue dialogue with Beijing on the topic.

The parliament’s fisheries committee was debating a non-binding resolution to be voted on in Strasbourg on Tuesday. It is seen as a way to push the commission and council – made up of the European Union’s 27 member states – to take action on the issue.

You may be eating seafood caught and processed by Uyghur forced labor

Original Article: The Guardian by Kenneth Ros – 13th October 2023.

The US government has taken some steps to block Chinese imports made with forced labor. Britain and the EU have done shamefully little.

Last month, Chinese diplomats sent letters – really threats – to discourage attendance at an event on the sidelines of the UN general assembly spotlighting Beijing’s persecution of Uyghur and other Turkic Muslims in China’s Xinjiang region. The childish tactic backfired, heightening media interest, but it highlighted the lengths to which Beijing will go to cover up its repression. A recent exposé on the persecution of Uyghurs should reinforce our determination to address these crimes against humanity.

A four-year investigation by the Outlaw Ocean Project pulls back the curtain on the massive use of forced labor in the Chinese government-backed fishing industry. Much of the study focused on people coercively kept on China’s distant-water fishing fleet, which holds workers at sea for months at a time in appalling conditions, often with lethal neglect. But the study also showed that seafood-processing facilities inside China are deploying Uyghur forced labor on a large scale.

Beijing’s persecution of Uyghurs has evolved in recent years, in part due to global scrutiny. At first, Chinese authorities established an extraordinarily intrusive surveillance state to identify “suspicious” activity such as excessive praying, wearing Muslim garb, or having contacts abroad. The reams of data collected were used to detain an estimated one million people to force them to abandon their religion, culture and language.

After initially denying their existence, Beijing laughably tried to pass these forced indoctrination camps off as “vocational training centers”. Some ingenious bureaucrat rubbed them off the Chinese equivalent of Google Maps, making their location easy to spot. But as people saw through these ploys, Beijing partially changed tactics. Some Uyghurs were convicted on trumped-up criminal charges and handed lengthy sentences in ordinary prisons. Others were released to the surveillance state, under threat of renewed detention should they act, well, too Uyghur. And some were moved into forced labor.

Most attention to that forced labor so far has focused on three big Xinjiang industries – cotton (20% of the world’s supply is grown there), tomatoes and polysilicon (used in solar panels). There is also evidence of the use of forced labor in the automobile and aluminum industries. Some Uyghurs were assigned to forced labor projects outside of Xinjiang – the better to deracinate them from their culture – but few details are known. The Outlaw Ocean Project shows us that the seafood processing industry is a major destination. Much of that seafood finds its way into Britain.

The US government has taken some steps to block such imports. The Uyghur Forced Labor Protection Act, adopted with overwhelming bipartisan support in December 2021, creates a rebuttable presumption against the import into the United States of any goods made in whole or in part in Xinjiang unless the products can be shown to be free of forced labor. Given the opacity of Chinese supply chains, a clean product is difficult to demonstrate.

Enforcement could be stronger – members of Congress fear that many goods made in Xinjiang are slipping by, especially as companies try to launder products through firms outside of China – but this presumptive bar is a powerful policy. The act also creates an “Entity List” for companies believed tainted by Uyghur forced labor. Clearly a good part of China’s seafood processing industry belongs on that list. Targeted sanctions should also be imposed on the officials and companies involved, as the separate Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act requires.

Neither the British government nor the European Union has followed Washington’s lead in restricting Uyghur forced labor by creating a presumption against imports from Xinjiang. The British government imposed targeted sanctions on four individuals and one company, but hid behind the impenetrability of the system to avoid doing more. A parliamentary bill proposing a presumptive ban is going nowhere.

The EU is planning to ban all products of forced labor – a good generic policy – but, again, without a presumptive bar for Xinjiang. In the meantime, while exports from Xinjiang to the US plummeted, exports to the European Union increased by a third in 2022.

In August 2022, Michelle Bachelet, then the UN high commissioner for human rights, issued a damning report that found that Beijing’s treatment of Uyghurs “may amount to crimes against humanity”. In October 2022, 50 governments including Britain signed a joint statement condemning these atrocities.

An effort to place her report on the agenda of the UN human rights council failed by a mere two votes, with disappointing abstentions by Ukraine, India, Mexico, Argentina, Brazil and Malaysia. The vote mattered so much to Beijing that Xi Jinping is reported to have personally telephoned four (unidentified) heads of state to urge a pro-China vote. It was only the second resolution ever voted down in the 16-year history of the human rights council.

Since then, global pressure over Beijing’s treatment of Uyghurs seems to have waned. No delegation in Geneva has tried again to persuade the UN human rights council to take up the issue. The new UN rights chief, Volker Türk, refuses even to repeat in his own words the findings of his predecessor, let alone to condemn these atrocities. He seems focused instead on raising funds for his office and pursuing the naïve if convenient belief that his quiet diplomacy suffices. The UN secretary general, António Guterres, is utterly awol, as he is for all forms of Chinese repression.

Now is no time to get complacent. Yes, Beijing is powerful, and the Chinese market is enticing, but no one should have to endure the persecution imposed on the Uyghur people. The new revelations about China’s fishing industry should compel all governments to redouble their efforts to press for these atrocities to end – and certainly not to be underwriting this persecution by purchasing its product.

A Frequent Culprit, China Is Also an Easy Scapegoat Using Uyghur Muslims in Seafood Industry

This story regarding China was produced by The Outlaw Ocean Project, a nonprofit journalism organization based in Washington, D.C. Reporting and writing was contributed by Ian Urbina, Joe Galvin, Maya Martin, Susan Ryan, Daniel Murphy and Austin Brush. It is being published as part of an international collaboration between news outlets. The reporting was partially funded by the Pulitzer Center.

Original Article: Inside Climate News by Ian Urbina – 16th October 2023.

TUMBES, Peru – On July 22, 2020, a journalist based in Santa Cruz, Ecuador, posted a photo on Twitter that purported to show hundreds of brightly illuminated Chinese ships fishing illegally near the Galapagos islands in a protected area.

“Massive presence of the fishing fleet #China” at the edge of the islands, the tweet warned, “a true floating city that captures everything in its nets.”

A media avalanche followed. Dozens of news organizations ran articles announcing the arrival of the Chinese armada and warning of the threat it posed to biodiversity in Darwin’s paradise. “Alarm over discovery of hundreds of Chinese fishing vessels near Galápagos Islands,” read a headline in The Guardian, citing the risks to “one of the world’s greatest concentrations of shark species.

One of the largest newspapers in Ecuador, El Universo, ran a story describing the ships as a “stealthy fleet,” which it said was inadvertently catching and killing marine life such as rays, turtles and sea lions. The Ecuadorian president at the time, Lenín Moreno, filed a protest to Beijing and vowed on social media to defend his country’s national waters.

But the tweet was inaccurate. There was no “discovery.” The Chinese fleet had been openly visiting the area annually for roughly a decade, and the photo in fact showed it fishing in Argentinian waters, not near the Galapagos. Not only that, most of the ships were squid-fishing vessels called jiggers, which do not use nets and do not typically catch sharks, unintentionally or otherwise, because their lines are not strong enough.

Roughly 13 hours after the original post, the reporter who published the Galapagos tweet issued a correction. The original tweet continued to circulate, however, and in the next week it was retweeted over 2,500 times. The correction, for its part, was retweeted fewer than 60 times. The photo with the faulty caption attracted more than 10,000 likes on Facebook and was also shared on Reddit.

It wasn’t unreasonable to suspect the Chinese fleet of illegal behavior. China has a well-documented reputation for violating international fishing laws and standards, bullying other ships, intruding on the maritime territory of other countries and abusing its fishing workers. In 2021, the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, a nonprofit research group, ranked China as the world’s biggest purveyor of illegal fishing.

But even a country that regularly flouts norms and breaks the law can also at times become a victim of misinformation. This is what seems to have happened in the case of the Galapagos tweet. “The larger issue here,” said Daniel Pauly, a marine biologist at the University of British Columbia, “is scapegoating.”

Such scapegoating creates problems, Pauly continued. When China feels that its fishing practices are being unfairly portrayed, he said, it becomes reluctant to engage with the international community on ocean issues. And China often pushes back by accusing its accusers of hypocrisy. And sometimes they’re right.

Nonetheless, a recent global investigation published in The New Yorker has intensified the critical light on China’s distant-water fishing fleet, quite especially its tendency toward labor abuses on many of its ships and in its processing plants. The investigation found a broad pattern of human rights and labor abuses, including debt bondage, wage withholding, excessive working hours, beatings of deckhands, passport confiscation, prohibiting timely access to medical care and deaths from violence.

More than 100 Chinese squid ships were found to have fished illegally, including by targeting protected species, operating without a license and dumping excess fish into the sea. Forced labor from China’s Xinjiang province is being used extensively in the country’s seafood industry.

The Chinese government has forcefully transferred more than a thousand ethnic minorities over 2,000 miles across the country to work in Shandong province, China’s most important fishing and seafood processing hub, in factories that supply hundreds of restaurants, grocers and food-service companies in the U.S., Europe, and elsewhere.

Products tied to workers from Xinjiang province are banned from import into the U.S., and the investigation has triggered international outcry because much of the seafood that is consumed in Europe and the U.S. is caught by Chinese ships or processed in the country’s plants.

Before the investigation published in The New Yorker, much of the criticism of China’s fishing fleet focused on environmental concerns. Over a third of fish stocks globally have been overfished, and Chris Costello, a professor of natural resource economics at the University of California, Santa Barbara, said that the West needs to be careful to take a historical outlook on the issue. He added that long before China emerged as the dominant fishing power, other countries, including in the West, fished unsustainably. “In other words,” he said, “overfishing is not a China problem.”

Rising ocean temperatures and increasing acidification driven by climate change have already degraded 60 percent of the world’s marine ecosystems, and the latest United Nations estimates are that more than half of all marine species may be close to extinction by 2100. These changing ocean conditions are pushing fish species into new and different waters, stoking more conflict on the high seas and in regional waters, and China, with its globally dominant fishing fleet, has increasingly become a target of criticism as countries vie for the ocean’s dwindling and shifting marine resources.

In response to claims of illegal fishing in the Chinese fleet in March 2023, Wang Wenbin, a spokesperson for the Foreign Ministry, said: “We call on the U.S. to do its own part on the issue of distant-water fisheries first, rather than act as a judge or police to criticize other countries’ normal fishing activities.”

In the six weeks after the Galapagos tweet, more than 27 news outlets ran similar stories about the threat posed to sharks and other marine wildlife by the Chinese ships. “Reports of 300+ Chinese vessels near the Galapagos disabling tracking systems, changing ship names, and leaving marine debris are deeply troubling,” Mike Pompeo, then the U.S. Secretary of State, tweeted on August 27, 2020. “We again call on the [Peoples’ Republic of China] to be transparent and enforce its own zero tolerance policy on illegal fishing.”

Some in the intelligence community, aware of how Pompeo was using misinformation to scapegoat the Chinese, grumbled when the tweet went out. But they understood the forces at play. “Sometimes,” one intelligence analyst said, “politics prevail.”

Outside the U.S. and E.U., other countries also capitalize on the fears tied to China, said Jonathan R. Green, the founder of the Galapagos Whale Shark Project. Within Peru and Ecuador, political parties play the Chinese off the U.S. for leverage. These parties often accuse each other of being too cozy with China or the U.S. In trade negotiations or development deals, for example, party officials within the Ecuadorian or Peruvian government sometimes cite the U.S. or China as a potential alternative partner that they can resort to if need be. Different fishing sectors in these countries also bend conservation or geopolitical concerns to their own advantage.

That may be one of the reasons that sharks played such a prominent role in the furor that followed the Galapagos tweet. The biggest culprits in the decline of shark numbers in Galapagos waters, Green explained, are not Chinese squid-fishing vessels but Ecuadorian and Peruvian tuna long-liners and local net-based trawlers and purse seiners. These boats are far more numerous, he said, their gear is equipped to catch sharks, and in many cases local governments legally permit them to target the animals.

“There’s a good reason that the tuna fishermen in Peru and Ecuador are often the ones to stoke the headlines about the Chinese squid ships,” he said. “It’s diversionary.”

Along the coast of Tumbes, Peru, outside a guard booth at a checkpoint in Puerto Pizarro, hundreds of shark fins were spread out on the concrete, drying in the sun.

Antonio Torres shook his head in disbelief at the sheer volume. Torres is responsible for inspecting the fins on behalf of the Peruvian Ministry of Production, the federal agency that polices the trafficking of protected wildlife. “There are like 300 sacks of shark fins,” he said, “and you know that in each bag there are about 200 sharks. It’s too much to be accidental.”

Sharks are a concern because three-quarters of their species are threatened globally with extinction. Ecuadorian waters around the Galapagos islands have the highest concentration of sharks in the world and are the only location where pregnant whale sharks are known to congregate. The islands, at the epicenter of El Nino and La Nina climatic extremes, are considered a natural laboratory for studying the impacts of climate change on sharks’ diets.

Trade and fishery data indicate that most of the shark fins passing through Tumbes come from Ecuador, which in 2007 changed its law to allow fishermen to land and sell fins or meat from sharks caught “incidentally” or by mistake, as “bycatch.” Fishermen can earn up to $1,000 per kilogram for shark fins sold in East Asia.

After being landed in Ecuador, the fins are typically trucked across the border into Peru, which is among the world’s largest exporters of the fins, and shipped mostly to Hong Kong and elsewhere in Asia for shark-fin soup. The scale of the trade is wildly underestimated, according to Jennifer Jacquet, an environmental-studies professor at New York University.

Between 1979 and 2004, she said, shark landings for the Ecuadorian mainland were an estimated 7,000 tons per year, or nearly half a million sharks, about 3.6 times greater than those that had previously been reported by the U.N. But the traffic is growing. In 2021, these exports were at a historic high, with 430 tons shipped, or the equivalent of more than 570,000 sharks killed.

China uses forced labor to process seafood that the world eats

Caption: A still from a video uploaded to a Chinese government Douyin account in 2023, showing the kick-off of a “labor program” organized by the local government in Kashgar. Source: Douyin, Kashgar Media Center – Public domain.

Original Article: de Correspondent by Ian Urbina – 15th October 2023.

In brief:

- At least four Dutch fish import companies trade in fish processed in Chinese processing factories where Uighurs perform forced labor. The companies NorthSeafood Holland, Seafood Connection, Kramers’ Seafood and Wout Taal Import BV import and distribute, among other things, coalfish, tuna, cod and squid from factories in the Chinese coastal province of Shandong, where Uyghur employees are known to work under duress. The fish is cleaned and packaged and is available under the brand name Iglo in the freezer section of branches of Albert Heijn, Jumbo, Aldi, Plus, Coop and Dirk.

- This concerns at least a thousand Uyghur forced laborers, who have been deported from their home province of Xinjiang since 2018 to work in ten fish processing factories in Shandong. The fish from those factories finds its way to at least twenty countries, including the Netherlands, the US, Spain, Italy and the United Kingdom. In addition to supermarkets, the fish also ends up in canteens of schools, government institutions and hospitals.

See also: New York Times 15th Aug 2023: Solar Company Says Audit Finds Forced Labor in Malaysian Factory.