McDonald’s and Amazon’s ties to alleged labor trafficking: five key takeaways

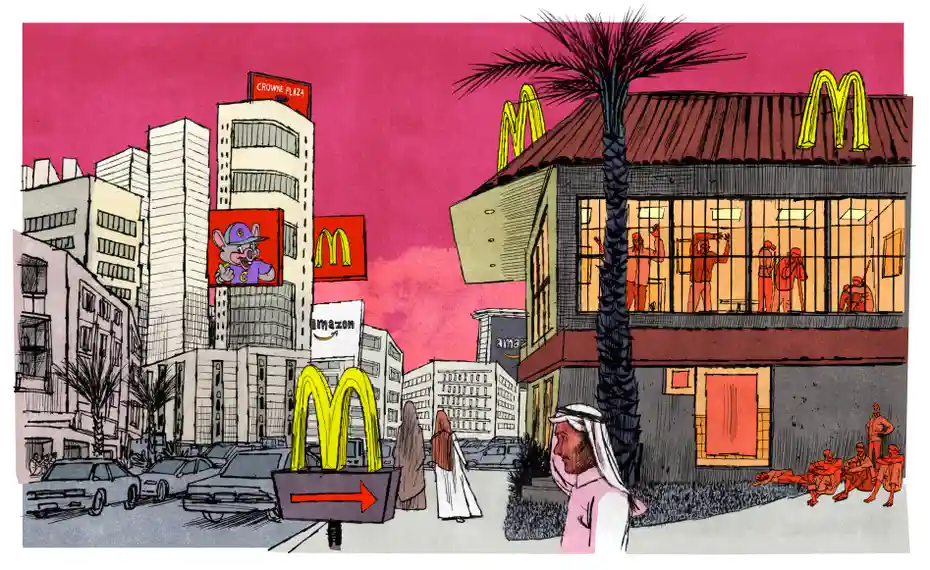

McDonald’s and Amazon have been tied to alleged labor trafficking. Foreign workers at the Middle East locations of US and UK brands allege low pay, harsh conditions, and a legal limbo with few protections.

Original Full Article: The Guardian by Alastair Gee – 10th October 2023.

- Revealed: Amazon linked to trafficking of workers in Saudi Arabia

- McDonald’s and Chuck E Cheese tied to alleged foreign worker exploitation

- Corporations are paying for worker abuse audits that are ‘designed to fail’, say insiders

Today the Guardian has published an investigation into labor conditions at the Persian Gulf locations of major US and UK brands, including Amazon, McDonald’s and the InterContinental Hotels Group.

Almost 100 current and former migrant laborers spoke to reporters, and many claimed they were misled into taking poorly paid jobs, subject to extortionate and arbitrary fees, or had their passports confiscated. These practices are broadly considered to be indicators of labor trafficking.

The workers were generally employed by franchise holders, other local partners or labor supply firms.

In response to questions from the Guardian, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and other media partners, Amazon said that some workers at its facilities had been treated poorly, and thanked them for speaking out. McDonald’s said it found the allegations “extremely troubling”. The InterContinental Hotels Group (IHG) and the Chuck E Cheese brand’s parent company, CEC Entertainment, said they took fair treatment of workers very seriously.

Here are five key takeaways from the stories.

Unbearable conditions as a contract worker at Amazon

More than 50 current and former workers described grueling experiences working at Amazon facilities in Saudi Arabia. All are migrant laborers from Nepal, and most claim they were told in their home country that they would be working directly for Amazon in the Persian Gulf. After they arrived they discovered they were instead employed by Saudi labor supply firms, and earned about $350 a month, or as little as one-quarter of what they say direct Amazon employees earned.

They say they worked long days in vast warehouses and were discouraged from taking water or toilet breaks. And many say often they were housed six to eight in a room in accommodations infested with cockroaches. The water supply was unreliable and salty and gave them rashes, workers say.

Arbitrary fees and penalties

A number of the workers claim they had no choice but to pay steep fees and fines that seemed capricious and amounted to months’ worth of their salaries.

Workers for McDonald’s and Amazon, for instance, say they were asked to pay a “recruiting fee” to independent employment firms in their home countries. The Nepali workers at Amazon say this could be as much as $2,300, even though the Nepali government mandates that such fees must be less than $85. Commonly, they say they took out loans to pay them, and felt they could not quit their jobs because they would be unable to repay the money.

When Amazon workers sought time off to travel to Nepal for births, funerals or other major events, the labor supply company they worked for required that they pay a penalty, or find another worker to be a “guarantor” who would be fined if they did not return. One man said he was asked to pay a $1,600 fine to attend his father’s funeral.

No way out

Fourteen workers at IHG-branded hotels and at Chuck E Cheese franchises claim that managers confiscated their passports. An assistant manager at Chuck E Cheese says this was done to make sure that staff did not “run away from the company and work in other companies”. Doing so is against the law in the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia.

IHG workers also say they were not permitted to resign if they received better employment offers elsewhere.

In limbo after being let go

Nepali workers at Amazon say they had minimal job security and that they were let go when business slowed. They claim they were then forced to leave the already dismal accommodations in which they were living and sent to grim new lodgings that did not have beds or internet service. They say they had no wages and could barely afford to eat.

The labor auditing industry is meant to protect overseas workers from labor abuses, and emerged in the 1990s after revelations that US companies were relying on sweatshops to produce goods abroad. But insiders from the industry says that auditing is frequently ineffective.

They and experts claim that auditing reports may be falsified, that auditors do not always act independently from the companies they are auditing, and that it is common for results of audits to be kept out of the public eye.

McDonald’s and Chuck E Cheese tied to alleged foreign worker exploitation and labor trafficking

Original Full Article: The Guardian by Katie McQue and Pramod Acharya 10th October 2023.

Over the years the world’s most powerful fast-food chain, McDonald’s, has twice honored a Saudi prince’s business empire with its highest accolade for its franchisees: the Golden Arch award.

Prince Mishaal bin Khalid al-Saud – who controls more than 200 McDonald’s outlets across Saudi Arabia – told CEO Magazine in 2018 that one of the secrets of his enterprise’s success is “ensuring a positive and favorable environment for our employees”.

Macrae Lee and Buddhiman Sunar recall a different environment. They say that they labored under harsh and unfair conditions at McDonald’s locations owned and operated by the prince’s Riyadh International Catering Corp (RICC).

Lee, who is from the Philippines, says RICC’s store managers ordered him to

put in as many as 22 hours a day and hundreds of hours of unpaid overtime. He was denied days off for rest, he says, even when he was sick with fever. When he tried to quit, a manager withheld paperwork that would have permitted him to find a new employer, he claims, leaving him jobless and begging on the street for food and water.

Sunar says he had to pay a stiff recruiting fee to an employment agent in Nepal to get a job at the prince’s fast-food outlets. Once he was in Riyadh, the Saudi capital, he worked 13- and 14-hour shifts with no breaks, he says. All the while, managers screamed abuse, he says, calling him “an animal” and asking: “Don’t you have a brain in your head?” If he stepped outside the restaurant, he says, he had to fill out an “incident report” explaining why. I felt like I was in jail

“I felt trapped,” Sunar, who left his job with the Saudi McDonald’s franchisee in 2022, said in an interview. “I felt like I was in jail.”

Lee and Sunar are among nearly 100 migrant laborers from Asia who say they’ve been subjected to repressive labor practices while working at the Persian Gulf locations of four well-known American and British brands: McDonald’s, Amazon, Chuck E Cheese and the InterContinental Hotels Group.

The current and former workers say independent employment agents in their home countries coerced them into paying exorbitant recruiting fees, while labor contractors and workplace supervisors in Saudi Arabia and other destination countries subjected them to abuses that included confiscating their passports and limiting their freedom to leave their jobs.

These practices are widely identified as indicators of labor trafficking, which is defined by the United States and the United Nations as using force, coercion or fraud to exploit workers.

The workers were interviewed as part of Trafficking Inc, a joint investigation by the Guardian US, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), NBC News, Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism and other media partners. The latest installments in the investigation reveal how some of the world’s most recognized companies may be complicit in labor abuses through their overseas subsidiaries, franchises and business partnerships.

Revealed: Amazon linked to labor trafficking of workers in Saudi Arabia

Original Full Article: Guardian by Pramod Acharya and Michael Hudson – 10th October 2023.

Momtaj Mansur wanted to go home to his mom and his brother and the pastures of Nepal’s southern plains. He felt like a prisoner, he says, in a roach-infested bunkhouse in Saudi Arabia, out of work, hungry and deep in debt.

The 23-year-old had come to Riyadh, the Saudi capital, in 2021 to work for one of the world’s biggest companies: Amazon.

Instead of his dream job, he says, he found low pay and misery. Amazon managers berated him, he says, for being too slow as he hustled across a vast two-story warehouse, grabbing iPhones and other items ordered by customers across the Arabian peninsula.

Then in May 2022, he says, he and many of his Nepali co-workers were abruptly let go from their jobs at the Amazon warehouse. They were 2,400 miles from home with no wages and little food.

Mansur says he pleaded with the Saudi labor supply company that held their employment contracts and had placed them in what amounted to temporary positions at Amazon: if there was no more work, let them return to Nepal.

The Saudi firm, he says, demanded he make a terrible choice. He could stay in a place that, for him, was “like a hell”. Or he could push his family back in Nepal deeper into destitution by paying a $1,300 exit fee, a penalty for leaving before his contract was done.

“I told them: either kill us or send us home, but don’t give us so much pain,” he says.

Momtaj Mansur is one of dozens of current and former workers who claim they were tricked and exploited by recruiting agencies in Nepal and labor supply firms in Saudi Arabia and then suffered under harsh conditions at Amazon’s warehouses.

Their accounts provide insight into how major American corporations profit, directly or indirectly, from employment practices that may amount to labor trafficking, which is defined as using force, coercion or fraud to induce someone to work or provide service.

Forty-eight of the 54 Nepali workers interviewed for this story say recruiters misled them about the terms of their employment, falsely promising they would work directly for Amazon. All 54 say they were required to pay recruiting fees – ranging from roughly $830 to $2,300 – that far exceed what’s allowed by Nepal’s government and run afoul of American and United Nations standards.

During their time in Saudi Arabia, these workers say, they were paid a fraction of what direct hires for Amazon’s Saudi warehouses earn, because labor supply firms were taking big cuts of what Amazon was paying for their labor.

Some workers say that after they’d been laid off from work at Amazon, their labor supply company sought to squeeze more money out of them, taking advantage of Saudi laws that give employers broad powers to control foreign workers’ freedom of movement. Mansur is one of 20 Nepalis interviewed for this story who say labor supply firms told workers they couldn’t go home to Nepal unless they paid exit fees that often equaled several months’ wages.

“We have already paid money to come here and we have to pay additional money to return?” one current worker says. “We feel trapped.”

Corporations are paying for worker abuse audits that are ‘designed to fail’, say insiders

Original Full Article: The Guardian by Abigail Higgins – 10th October 2023.

Before he began the interviews, Ahmed swept the room for cameras and recording devices. He then invited the workers in, one by one, spending about 10 minutes talking with each.

They were employed at a factory in the Middle East that supplied goods for a major American company – and it was Ahmed’s job, as an outside auditor, to uncover any labor abuses. Often, before he could even ask a question, the staff members hastened to assure him that they were happy with their jobs.

Their eagerness made him suspicious.

As Ahmed coaxed answers out of one worker, a security guard at the factory, a different picture emerged. He said he had worked 26 days straight, with long hours, no days off and no overtime pay. He was scared – if anyone found out he was talking honestly, he might lose his job. When Ahmed scrutinized the attendance and pay records the company provided him, he found they had been falsified, in part because security footage showed the man was truly enduring a grueling schedule. The names of all the workers were missing from attendance records, making it impossible to decipher whether hours and wages were fair.

Ahmed was upset but not surprised. He’s audited this same company more than 50 times across the region, and estimates that in at least 10 cases he found some form of labor abuse. They included signs of forced labor, such as confiscated passports so workers weren’t able to leave the country. He was rarely able to take action.

In this instance, he informed a manager at the factory that it had failed to comply with basic labor standards. In response, the manager told him to change the finding. The audit needed to find that the company was free of labor abuses, he said to Ahmed, otherwise it might lose business.

“I was very disappointed,” Ahmed says, adding that the factory did not invite him back for a follow-up assessment and that he suspects it hired a different, more compliant auditor.

US companies “use audits to pretend that they are protecting people but actually they’re just doing business and trying to minimize cost as much as they can”, according to Ahmed.

American and European firms with overseas operations have turned to auditing firms, like the one Ahmed works for, to investigate conditions at their factories and produce an assessment sometimes known as a social audit.

But insiders and observers say auditing companies are failing at their job, and are part of a broader system focused less on safeguarding workers than protecting companies – and their bottom lines – from costly public relations scandals.

Labor abuses persist in the global operations of many big companies, as an investigation published today by the Guardian US, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, NBC News and Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism has revealed. In interviews with the reporting partnership, nearly 100 workers describe an array of unfair and repressive labor practices within the Persian Gulf footprints of Amazon, McDonald’s, Chuck E Cheese and the InterContinental Hotels Group.

Workers accuse Middle East operations of McDonald’s, Chuck E. Cheese and other Western brands of labor abuses

Hundreds of McDonald’s franchise restaurants in Saudi Arabia employ thousands of workers. Image: Photo by Lynsey Addario/Getty Images.

Nearly 100 current and former workers interviewed by ICIJ reported being subjected to practices that are widely considered indicators of labor trafficking.

Original article: ICIJ by By Katie McQue and Pramod Acharya.

Over the years the world’s most powerful fast-food chain, McDonald’s, has twice honored a Saudi prince’s business empire with its highest accolade for its franchisees: the Golden Arch Award.

Prince Mishaal bin Khalid al-Saud — who controls more than 200 McDonald’s outlets across Saudi Arabia — told CEO Magazine in 2018 that one of the secrets of his enterprise’s success is “ensuring a positive and favorable environment for our employees.”

Macrae Lee and Buddhiman Sunar recall a different environment. They say that they labored under harsh and unfair conditions at McDonald’s locations owned and operated by the prince’s Riyadh International Catering Corp.

Lee, who is from the Philippines, says RICC’s store managers ordered him to put in as many as 22 hours a day and hundreds of hours of unpaid overtime. He was denied days off for rest, he says, even when he was sick with fevers. When he tried to quit, a manager withheld paperwork that would have permitted him to find a new employer, he claims, leaving him jobless and begging on the street for food and water.

Sunar says he had to pay a stiff recruiting fee to an employment agent in Nepal to get a job at the prince’s fast-food outlets. Once he was in Riyadh, the Saudi capital, he worked 13- and 14-hour shifts with no breaks, he says. All the while, managers screamed abuse, he says, calling him “an animal” and asking, “Don’t you have a brain in your head?” If he stepped outside the restaurant, he says, he had to fill out an “incident report” explaining why.

“I felt trapped,” Sunar, who left his job with the Saudi McDonald’s franchisee in 2022, said in an interview with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. “I felt like I was in jail.”

Lee and Sunar are among nearly 100 migrant laborers from Asia who told ICIJ that they’ve been subjected to repressive labor practices while working at Persian Gulf locations of four well-known American and British brands: McDonald’s, Amazon, Chuck E. Cheese and InterContinental Hotels Group.

The current and former workers say independent employment agents in their home countries coerced them into paying exorbitant recruiting fees, while labor contractors and workplace supervisors in Saudi Arabia and other destination countries subjected them to abuses that included confiscating their passports and limiting their freedom to leave their jobs.

These practices are widely identified as indicators of labor trafficking, which is defined by the United States and the United Nations as using force, coercion or fraud to exploit workers.

The workers were interviewed as part of Trafficking Inc., a joint investigation by ICIJ, the Guardian US, NBC News, Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism and other media partners. The latest installments in the investigation reveal how some of the world’s most recognized companies may be complicit in labor abuses through their overseas subsidiaries, franchises and business partnerships.

See also: 22nd June 2023: Activists pour cold water on improved human trafficking ranking for Malaysia.