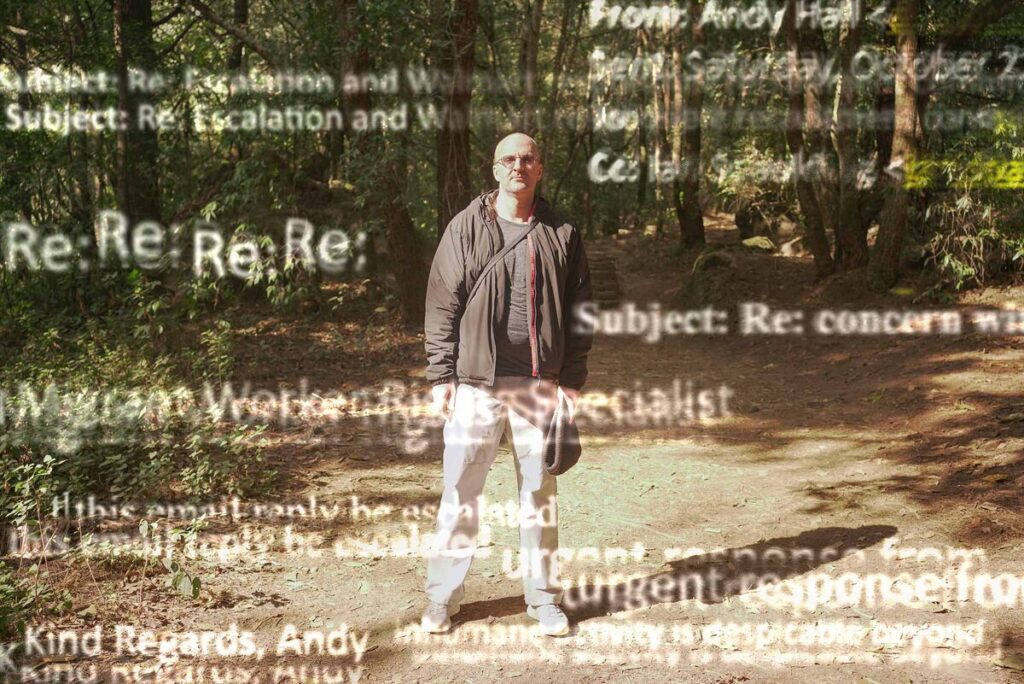

15th February 2024: Bloomberg Businessweek Feature – Andy Hall ‘Playing God’: This Labor Activist’s Relentless Emails Force Companies to Change

Andy Hall scours the global supply chain on behalf of exploited workers. If you ever hear from him, just know he won’t go away quietly.

Note from Andy Hall:

Thanks Anders Melin and Bloomberg Businessweek for telling ‘our’ story about ‘our’ work. As behind me making this important work possible every day are indeed so many ‘invisible’ and ‘inspiring’ activists, and also the victims of forced labour. Hope this article creates more understanding about our work!

Original Source: Bloomberg Businessweek Feature by Anders Melin – 15th February 2024

The three men sped in silence through the sultry Malaysian night. In the back seat was Dhan Kumar Limbu, a 32-year-old factory worker. In the front were two officials from his employer, an electronics maker called ATA IMS Bhd. The car snaked through the streets of Johor Bahru, an industrial hub, and stopped at a police station near the heart of the city. Limbu stepped out with a sinking feeling in his stomach. He knew he was in trouble.

Like so many other Nepalese migrant workers, Limbu toiled in the vast warren of global supply chains. For much of the past nine years, he’d worked 12-hour shifts plus overtime, seven days a week, at ATA, a contract manufacturer whose most important client was the British vacuum maker Dyson.

He’d recently been put in touch with an associate of Andy Hall, one of Southeast Asia’s best-known human-rights activists. Fed up with his drudgery, Limbu had begun sending pictures of the factory’s interior, as well as internal documents such as production lists, to show that parts of Dyson products were made by workers laboring under gruesome conditions. Now, somehow, ATA was onto him.

Up a few flights of stairs, two police officers began interrogating him. Why did you leak such important information, they demanded. Because Andy Hall’s associate said he could help me, Limbu responded. The cops slapped him. One led him into another room and told him to sit on the floor, then planted his foot on Limbu’s legs and began lashing the soles of his feet with a rubber hose. Another round of questioning followed. Then the lashings resumed.

Limbu back home in Nepal

In sworn testimony about the incident, Limbu would later recount that an ATA executive showed up at the station. I gave you a job that helped feed your family, he told Limbu. Why did you share information with these bad people?

ATA has acknowledged that Limbu was taken to the police station but said a law firm probed the matter and concluded his allegation about being beaten was “unsubstantiated.” The company didn’t respond to requests for comment, nor did the Royal Malaysia Police. The ATA executive, who no longer works at the company, said Limbu’s account is untrue but declined to respond to specific questions.

At the time, in June 2021, ATA’s leaders had good reasons to worry about Hall. A 44-year-old Englishman with legal training, he’d recently helped expose widespread forced labor in Malaysia’s rubber glove industry, costing companies more than $800 million in revenue. Now he was after ATA. He’d sent information alleging worker mistreatment to US Customs and Border Protection (CBP), which had opened an investigation. He’d also passed it to Dyson, to government and embassy staff and to journalists. ATA’s share price had begun to tumble.

“Everything is urgent. And it should be”

This was the Hall method. For more than a decade, he’d bounced around Southeast Asia, ferreting out alleged forced labor and demanding change in relentless email salvos. His missives came from a simple Gmail address. They included a Nepalese cellphone number and a title—“migrant worker rights specialist”—that betrayed no formal affiliation with anyone. He was said to live in Kathmandu, but often surfaced far from the Himalayas: in Brussels, Indonesia, London, Myanmar, Thailand and, now, Malaysia. He hurled accusations and confidential information into the open without restraint.

These tactics had won him both allies and enemies in Asia and beyond. They’d also prompted recurring questions—about his methods, his motives and his money. What was this man’s deal, really?

That night at the police station, the ATA executive told Limbu: Hall doesn’t care about you; he’s using you. He asked Limbu to sign a statement saying Hall had paid him to leak the information. Otherwise, the executive warned, Limbu would be charged with terrorism and put away for life.

“Andy Hall,” the executive said, “is a bad person.”

On any given day, more than 150 million people wake up in a foreign country and either go to work or look for employment. Among them are Filipino sailors on cargo ships; Indonesian maids in Hong Kong and Singapore; Mexicans picking cherries in Washington state; and Nepali security guards in the skyscrapers of Dubai.

Many who fill these jobs are under the heel of their employers because of restrictive work visas and debts owed to recruitment agencies. Pay is often low. Racism, laws and language barriers can curtail access to local police, courts, unions and social services. And the workers are often replaceable, because the supply of people willing to choose toil abroad over poverty at home is vast.

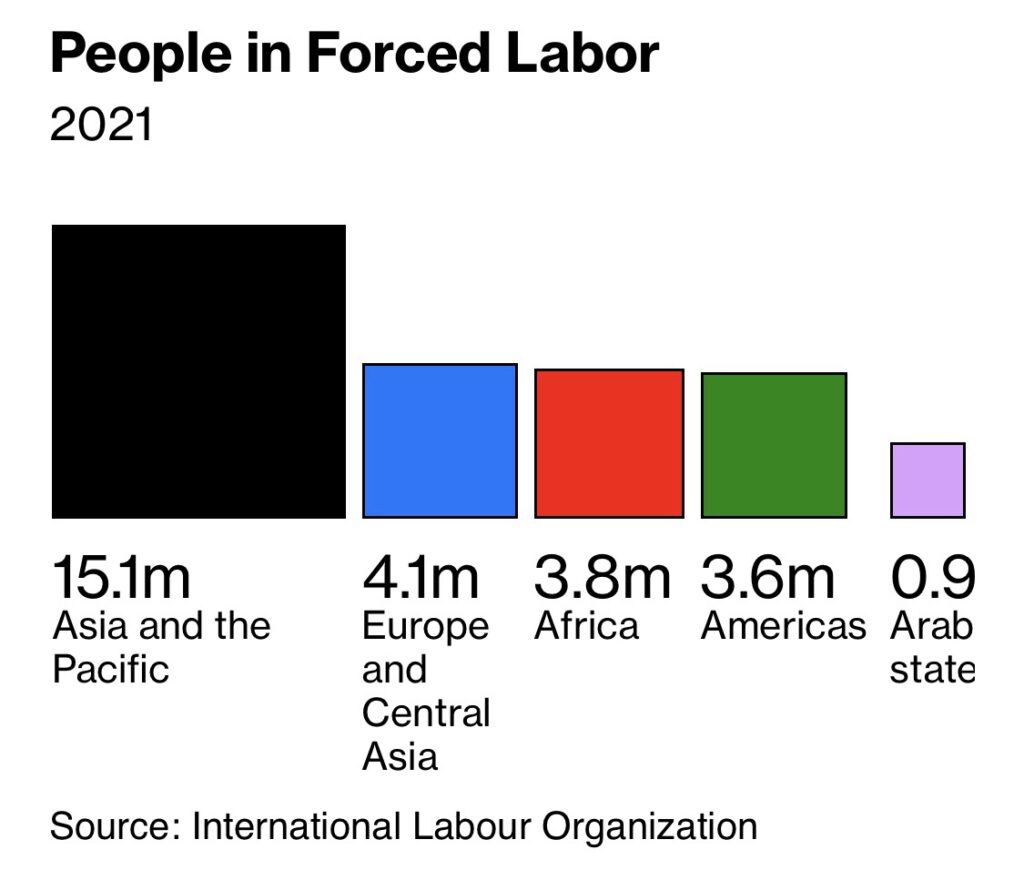

These factors make migrant workers particularly vulnerable to forced labor. The International Labor Organization estimates 28 million people globally are shackled to jobs through fraud or coercion; more than half of them are spread across Asia and the Pacific.

People in Forced Labor 2021

Hall says almost everyone, especially those leading a comfortable life in the West, has incentives to ignore labor abuses. While workers in far-flung geographies suffer, companies collect bigger profits, investors enjoy higher share prices, and consumers get cheaper products. “Most people accept that this happens in the world,” Hall says. “But I feel the urgency of these issues. Everything is urgent. And it should be.”

Hall doesn’t have a nonprofit or a consulting company or even an office. He doesn’t have investors or a boss or a board of directors. It’s just him, sometimes aided by a small network of activists and former migrant workers, running on funds from a few consulting gigs and a seemingly bottomless sense of indignation. He channels this into blunt, insistent emails, written in lawyerly English that more than occasionally dips into rudeness. They go out, sometimes dozens a day, to lawyers, lawmakers, journalists, unions, trade groups, asset managers, ambassadors and corporate executives. On any email an untold number of people may be blind-copied. Hall is no big believer in confidentiality.

Andy Hall at a 2016 rally in his support in Bangkok

“In the past weeks we received 20+ emails from you,” a social responsibility executive at Amazon.com Inc. once wrote to Hall—one of the hundreds of emails he shared with Bloomberg Businessweek for this story. She asked him to stop blind-copying her and her colleagues on messages with labor-abuse allegations against companies, some of which sold products on the platform. “Amazon does not consider that manner of engagement an appropriate channel for surfacing concerns,” she wrote. She invited him to send his concerns directly to her, and only her.

“Do not tell me what to do and what not to do,” Hall shot back. “It is not up to me to spoon feed you or Amazon information in a package that you feel is appropriate.” He was doing Amazon a favor, he went on, by filling the gap “of your poor due diligence and monitoring of your suppliers who are engaged in forced labour.” The Amazon representative didn’t respond to a request for comment.

It’s perhaps the perfect Hall story. Supporters say it demonstrates his commitment, his tirelessness, his refusal to kowtow to power. Critics say it primarily shows his blustery narcissism. “It’s like religious fervor,” says a diplomat in Kuala Lumpur, who asked to remain anonymous to avoid drawing Hall’s ire. “He’s like a preacher standing in the town square, shouting at all the nonbelievers.”

This diplomat says that even though he appreciates it when Hall shares information, he doesn’t trust the man. If Hall toned down the rhetoric and respected confidentiality, the diplomat allows, he might change his mind.

But if Hall did, would people still pay attention to him? The diplomat ponders the question.

“Probably not.”

Here is Hall’s play: Leads about migrant workers enduring abuse come to him through whistleblowers, his network and his travels. He collects evidence. Then he emails the company in question and demands immediate action. He emails again. And again. And again. “I always write to the most senior people,” he says. “They don’t want it in writing. They say, ‘Talk to my compliance team’ or whatever, but I keep copying them and say, ‘You can delete me, but I’m going to keep emailing you.’ Otherwise they can claim they didn’t know anything, but I make sure they do.”

Some companies acknowledge the problems Hall identifies and present a plan to resolve the matter. Others don’t. They soon see more and more people copied on increasingly caustic missives—a gun-to-the-head approach that one of Hall’s friends, only half-joking, calls “Andy Hall playing God.”

“I am writing with concern about ongoing recruitment of foreign workers by your company,” Hall wrote in 2022 to Mamee-Double Decker Sdn Bhd., a Malaysian snack maker, alleging some workers had been squeezed by recruitment agents. “I would request the urgent response” within 48 hours, “prior to escalation as may be considered appropriate given the seriousness” of the matter.

Mamee’s executives said they would investigate, but Hall wasn’t satisfied. Six days later, he wrote that he’d relayed his allegations to the company’s overseas buyers, including Walmart Inc. and Woolworths Group Ltd., the Australian supermarket chain.

“We are ready to collaborate and have shown that intention from Day 1,” the chief executive officer, Pierre Pang, replied. “But we will not be bullied into any threats unjustifiably.”

“Capitalist companies are too often the bullies of this world,” Hall fired back, copying two executives from Woolworths. “I am not a bully, and my actions are not unjustifiable.” Furthermore, he wrote, “If the situation isn’t resolved promptly and effectively, I also reserve the right to escalate to public campaigning and media coverage of this issue.” A Mamee representative says that the company investigated and reformed its recruitment process, and that it didn’t disagree with Hall’s escalation: “We know that he is an independent party and not within our sphere of control.”

“He’s stepped on very important toes”

Why don’t people just ignore him? Some government and corporate officials can’t; they’re obligated by law or policy to examine allegations that come their way. Others realize Hall has alliances in halls of power—he has, they know, prompted multiple US federal investigations. But perhaps more than anything, it’s simply because of his style. He’s prolific, persistent and uncontrollable. “Dealing with Andy is terribly hard,” says the head of an ethical-trade advisory company. “But if you don’t speak with Andy, it’s worse.”

About two years ago, Hall learned that British farms were recruiting seasonal workers from Southeast Asia for the harvest. Many of the workers took on debt to pay steep fees to recruitment agencies, putting them at risk of financial ruin if they left the jobs.

Hall was infuriated. How could European companies and governments credibly hold their Asian counterparts to account if they couldn’t even do things right themselves? He tipped off journalists; articles followed. Later he worked with CCLA, the largest UK fund manager for charities, to rally big asset managers to sign a public statement calling on supermarket chains to help ensure no seasonal laborers would have to pay for a job. Ten institutions with more than $900 billion in total assets ultimately signed it—a puny turnout, Hall thought. “Usually we get really good pickup for these things,” he says. “But this time it was so, so little.”

He decided to share some confidential information with reporters at the Financial Times detailing the behind-the-scenes lobbying of asset managers. The paper subsequently ran a piece naming asset managers who’d been approached by CCLA and declined to sign the statement.

“Calling them out, you know,” Hall remembers. “And of course people in the group got upset.”

He frowns.

“So they reached out to me and said, ‘Andy, did you share this with the FT?’ And I said, ‘Yes, I shared it with them on background.’ They went ballistic and said, ‘We’ll never deal with you again.’ But now they’re going to meet with me on Friday.”

He throws up his hands.

“When I see blood, I have to go for it.”

From his base in Nepal, Hall investigates alleged forced labor across Southeast Asia.

Hall grew up in the small British town of Spalding. His father worked for Caterpillar, his mother in a newspaper shop. Hall was bookish. He played the cornet and studied law at University College London. He anticipated a lucrative career in corporate law. But a brief relationship with a person from the city’s underclass, living a broken life of drugs and poverty, knocked him off that course.

After graduating in 2001, he pursued a doctorate in corporate criminal responsibility, then abandoned it. “I’m just sitting and reading books and writing things,” he recalls thinking. “I’m not living a real life. It’s pointless.”

Unsure about what was next, Hall flew to Thailand in 2005 to visit a friend. He loved the country and its people but felt out of place as a tourist. Ruffling through newspapers one day, he read about a nonprofit helping workers, many of them from Myanmar, who were injured on farms and construction sites in the north of the country. Hall contacted the organization and offered to help. He quickly took to the work. He rented a studio apartment in Chiang Mai with a bed, a desk and a cold-water shower, and made Thailand his home for the next decade.

Around this time, the West was waking up to the impacts of race-to-the-bottom outsourcing. Reports about the sweatshop conditions at East Asian factories making Nike shoes had ricocheted across the globe in the 1990s and early 2000s, drawing a clear line from the comforts of the world’s affluent to the plight of its poor.

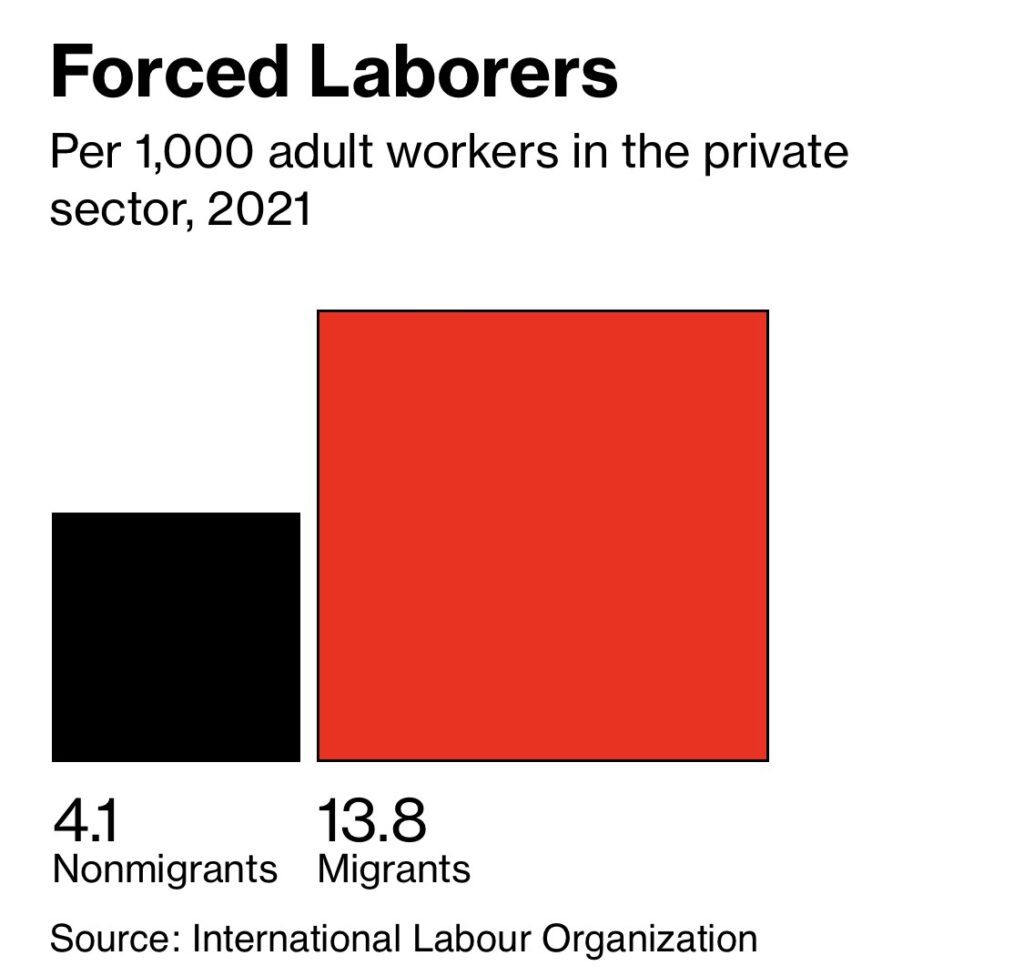

Forced Laborers Per 1,000 adult workers in the private sector, 2021

Hall started focusing on worker abuses linked to global supply chains. He cycled through research and advisory jobs, founded a nonprofit called the Migrant Workers Rights Network and spoke at conferences, establishing contacts with people at the nexus of governments, companies and investors. Even in the ranks of human-rights defenders, home to many curious characters, Hall cut a unique figure. He built a reputation as a tenacious researcher who, on a shoestring budget, could find evidence of forced labor almost anywhere. And when he dug up something significant, he immediately began making noise. The time to act was always now; the means of action always confrontation.

That approach has created a rift with some who share his goals. Many of his critics say that lasting impact often is achieved through quiet and deliberate collaboration between civil society, governments and companies—not by public agitation. Hall, for his part, says many nonprofits are bloated, bureaucratic and beholden to donors. He says many have lost sight of their purpose. What good is yet another report or panel discussion when there are migrants across town who languish in abusive conditions and need help now?

In 2013 a watchdog in Helsinki published a report detailing alleged labor shortcomings at three Thai food companies that supplied Finnish supermarket chains. It was largely based on field research led by Hall. Shortly after, one of the suppliers, Natural Fruit Co., pressed defamation charges against him in Thailand.

The cases, two criminal and two civil, put Hall at risk of a prison sentence and more than $10 million in damages. He’d made allies, however, and they mobilized. Numerous unions and human-rights organizations spoke up. The United Nations demanded that the prosecution be investigated. A throng of reporters crowded the steps of a courthouse in Bangkok on the day in 2016 when Hall was convicted in one of the cases. Shortly after, the European Parliament passed a resolution in his support.

Hall appealed his conviction, and all charges were eventually dismissed. The process took an emotional toll—but it also burnished his image globally and expanded his influence. “He’s stepped on very important toes many, many times,” says Heidi Hautala, a vice president of the European Parliament. “And that’s why he always has my attention.”

For some people in Asia, however, the whole affair left a bitter aftertaste. The dominant narrative—righteous Westerner versus malevolent Thai company—glossed over the fact that worker conditions in the region often stem from ever-increasing demands by companies in richer countries. And many local activists who aren’t White men with British accents and law degrees endure far worse without a shred of attention. “For every Andy we hear about in the international press, there are 10 or 15 others you never hear about,” says Puvan Selvanathan, a human-rights expert and former UN official.

But, Selvanathan adds, “it would be petty, or disingenuous, to deny the exposition of the issue because the messenger is the wrong color. Use whatever lever you’ve got. The issue is bigger than all of us.”

“If they don’t do what I want, I’ll just leak stuff”

Anyone hanging around Malaysia’s main industrial areas in late 2018, right before dawn or dusk, might have spotted Hall waiting outside factory gates. Once workers walked off their shift, he’d make his move.

“I would just walk up to them,” Hall says. “ ‘Hi, I want to speak about the conditions at your work. Can I see your work permit? Can I see your passport?’ Honestly, I was so blatant. Some were scared, but some would cooperate.”

Hall, rattled by the legal cases, had left Thailand. In Malaysia he was mapping worker conditions on behalf of a Swedish watchdog. He soon picked up two big leads: allegedly dreadful conditions at ATA and alleged abuse at several of the country’s makers of rubber gloves.

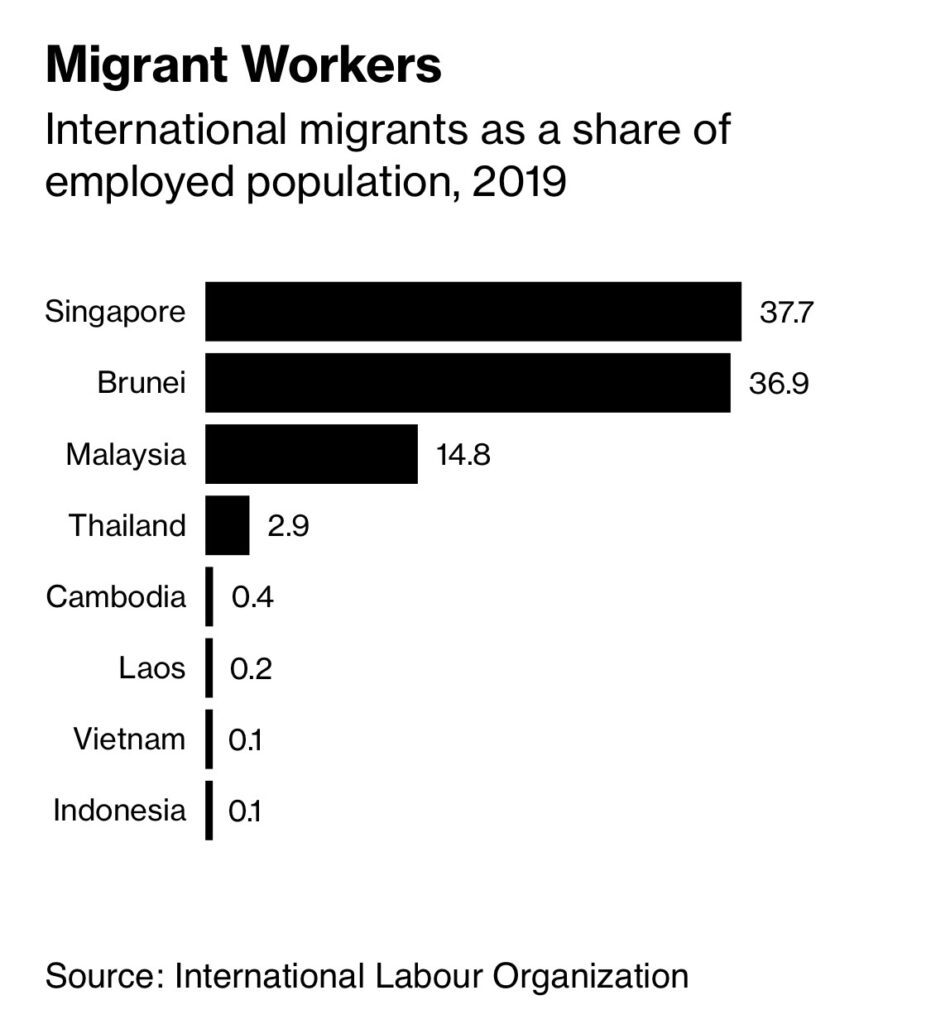

Foreign workers fill many of Malaysia’s hardest jobs. The country officially has 2.7 million migrant workers—around 15% of its workforce—but by some estimates the actual figure, also counting undocumented workers, is twice as high. When Hall arrived, thousands of migrants worked in the country’s disposable glove industry, which churned out 2 of every 3 rubber gloves used globally.

Migrant Workers – International migrants as a share of employed population in 2019

Hall scurried around to different factories and worker hostels, collected testimonies and documents, and emailed journalists. Within weeks, the Australian Broadcasting Corp., the Guardian and Reuters published stories about alleged labor abuse at two glovemakers. The companies denied they were violating workers’ rights, and the government said it found no wrongdoing. “I can assure that no foreign workers were forced to work overtime in the factories,” M. Kulasegaran, then Malaysia’s minister of human resources, said at a press conference, seated next to the billionaire founder of Top Glove Corp., the industry leader.

Hall didn’t relent. He knew that hospitals around the world used Malaysian gloves. He turned to the mightiest customer of them all, the US government, and began peppering its customs agency, CBP, which can detain imports suspected to be made with forced labor. Just as the agency began picking up the lead, Covid-19 appeared, and demand for gloves surged. The plight of the workers producing them suddenly became a global story, and there was Hall, feeding worker testimonies and caustic quotes to any journalist who asked.

In the end, CBP investigated at least five Malaysian glovemakers based on information from Hall, documents show. It later issued withhold-release orders—detainment of imports—on products from at least six companies. An industry group estimates the bans cost the glove companies as much as $860 million in revenue. In addition, they collectively paid more than $100 million to current and former migrant workers to remedy recruitment fees and invested in better housing and benefits.

Glovemaker share prices, after spiking in 2020, were now falling. Some of Hall’s antagonists suggested that this might have been the goal all along. Was he a short seller, or working in the service of one? Suspicions escalated in late 2021 after Credit Suisse Group AG hosted a client call on which Hall was quizzed about his work. He mentioned a few companies he thought were mistreating migrant workers. Some of the stocks promptly fell, erasing $500 million of market value. Also around this time, Top Glove announced that Hall would become an adviser—a “critical friend”—to help it improve worker conditions.

Today, Hall is a consultant to four companies in Thailand and Malaysia, each paying him monthly retainers of a few thousand dollars. Three declined to comment for this article; the fourth, palm oil company Sime Darby Plantation Bhd., says that Hall didn’t request a fee and that it used an external adviser to set a rate for him. Hall says he sometimes freelances for labor rights advisory companies, earning a daily retainer, and receives speaker fees.

Where critics see conflicts of interest, or worse, Hall sees pragmatism. Actual change can only happen inside companies. He has knowledge they need. If they want to pay for his time, fine—but he says he never asks for money. “I’m not satisfied to be just on the outside as a critical actor,” he says. “I want to be on the inside as a constructive actor, too. I want to be everywhere, in fact.”

And, he adds, “if they don’t do what I want, I’ll just leak stuff.”

On a sunny day in London last July, Hall stood outside the Royal Courts of Justice. With his buzz cut and glasses, in a gray suit he’d bought secondhand, he looked more like an anonymous British middle manager than a controversial arbiter of right and wrong. He was there to observe a hearing in a case involving the alleged mistreatment of Limbu and 23 other former employees of ATA. The workers, all from Nepal and Bangladesh, had sued Dyson, alleging the company had failed to protect them from forced labor. They’d filed the case in London, arguing they had no shot at a fair trial in Malaysia. Dyson has disputed this and said Malaysia would be a more appropriate venue for the case.

Hall had begun his campaign against ATA four years earlier with an email to Dyson. “A reliable whistleblower and numerous other sources” had alerted him to unethical recruitment practices of foreign workers at ATA, violating Dyson’s policy, Hall wrote. He copied several UK government officials.

Dyson assured Hall it was looking into his claims. “We have investigated your allegations regarding ATA carefully and have concluded that they are not factually correct,” a company official later wrote to Hall, adding that Dyson has “stringent processes and initiatives in place to ensure best practice in our supply chain.”

Hall was busy with the glovemakers at the time and let the matter rest. But in April 2021, he fired off a new burst of emails.

No company, no office, no staff. Hall does his work largely alone

No company, no office, no staff. Hall does his work largely alone.Photographer: Rajneesh Bhandari for Bloomberg Businessweek

“Workers are reporting no remediation of very high levels of recruitment fees,” along with “pockets of very poor quality accommodation standards,” he wrote to Dyson. That month, CBP confirmed in a letter to Hall that it had opened an investigation into ATA. Dyson’s global sustainability director told Hall that the company was following up and that it “treats matters of supply chain worker welfare, including ethical recruitment” with utmost importance.

In November 2021, Dyson announced it would terminate its relationship with ATA. In a statement at the time, Dyson said it recently had been informed of “allegations about unacceptable behavior” by ATA staff on June 28 that year—the day Limbu was brought to the police station. Dyson also said it terminated the contract after an audit of ATA, which included interviews with more than 2,000 workers, identified issues that the supplier didn’t address quickly enough. ATA has denied all accusations that it mistreated workers. The company didn’t respond to a request for comment.

This situation illustrates the unpredictability of Hall’s confrontations. He’d brought attention to a sliver of the supply chain for popular consumer products used globally. Dyson’s contract termination was a powerful message that alleged mistreatment of workers can have consequences. Moreover, Hall’s research had helped pave the way for the former ATA workers’ legal case, which was a novel attempt to move accountability for alleged worker mistreatment up the economic food chain. Many companies have been sued for harm done by foreign subsidiaries. Limbu and his former colleagues wanted to apply the same principle to Dyson for alleged wrongdoing by its independent supplier, saying Dyson had profited from their plight. Dyson has said “these allegations relate to employees of ATA, not Dyson,” and has vowed to defend itself in whichever jurisdiction a case is brought.

At the same time thousands of workers, and families they supported, had lost their source of income, and Limbu ended up in police custody after sending Hall information. (He did sign the statement saying Hall had paid him for sending documents; both say no money changed hands.) Anticipating the possible fallout from a release of sensitive information is a key tenet in human rights. Some point to a principle borrowed from medicine: First, do no harm. In the eyes of some people familiar with Hall’s work, here he falls short.

The judgment came down in October: The case couldn’t proceed in the UK. It’s “far more appropriate for these legal issues to be decided by Malaysian judges,” and the workers had good chances of finding local lawyers, the ruling said.

The next day, Hall sounded resigned. He reflected on the scene he’d witnessed in the London courtroom. A phalanx of lawyers had been present, representing thousands of pounds of fees every hour. They’d brought stacks of binders with evidence, hinting at the depth and cost of their preparations. To Hall, it was another example of vast efforts and money spent bickering over who was responsible for alleged worker abuse without considering the workers’ actual immediate needs.

The 24 plaintiffs hadn’t specified how much compensation they wanted for alleged personal harm suffered while in ATA’s employ, but most else of what they asked for—unpaid wages, holiday pay, recruitment fees and more—had been calculated. It amounted to roughly $300,000.

Behind that figure were two dozen men and women who’d harbored hopes for a better life, who’d weighed bleak prospects at home against the risks and sacrifices of working abroad. Dyson’s contract termination wiped out about 80% of ATA’s annual revenue and devastated its stock, so it was clear to Hall that any compensation would have to come from Dyson. But legal cases can take years. Restitution, if it ever came, was far into the future.

This hung over Hall. “The most important thing is now,” he said. “They’re desperate now. They need support now.”

His role, Hall often says, is to put information into the world, with an understanding that he can’t control how the world reacts to it. Still, it seemed to sting. “I think it’s the first time in my life that the outcome has been so negative,” he said.

He went quiet for a moment.

“But I’m just one actor,” Andy Hall said. “You just throw sand in the air, and you can never be sure which grain goes where.” —With Joy Lee and Anuradha Raghu

See also: 12th Jan 2024 TBIJ: UK government ‘breaching international law’ with seasonal worker scheme, says UN envoy

See more: 10th July 2023: Allegations of forced labour and dangerous conditions at Dyson Malaysian factory